|

Spring 2000 (8.1) The Institute

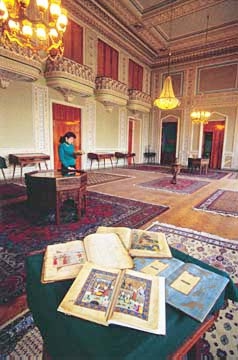

of Manuscripts

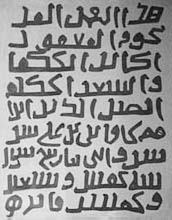

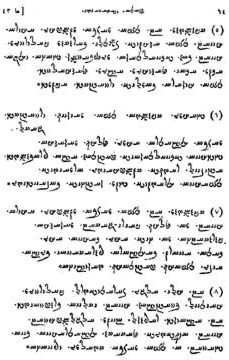

Left: Ancient script of the 12th century Right: Avestian alphabet or Pahlavi script Old Turkic The nomadic Turkic tribes that inhabited Azerbaijan between the 4th and 8th centuries AD used a Runic script, which is also indigenous to some of the Germanic peoples of Northern Europe, Britain, Scandinavia and Iceland. Examples of this type of writing can be found carved on the Garga Dashi rocks near the Nuvadi settlement. Azerbaijanis resided in this district of Megri in contemporary Armenia before they were ousted about ten years ago. Carvings in the Runic script have also been found in the North Caucasus mountains and Altay. This alphabet has been carefully studied and documented.

Right: Notice for Hajibeyov's music comedy, "Arshin Mal Alan" (The Cloth Peddlar), early 20th century. Arabic Introduced After the Arabs conquered the region and brought Islam in the 7th century AD, the Arabic alphabet became the standard script. The Institute has 3,000 samples of early Arabic-script manuscripts, dating as far back as the 9th century. The ones I've studied the most are the 70 handwritten texts devoted to medicine, including Tibbname (Book of Medicine), written by Muhammed Yusif Shirvani in Azeri in 1712. Other Arabic-script works feature poetry by writers such as Fuzuli, Nasimi, Khatai, Saib Tabrizi and Vagif. There are also books in the fields of astronomy, astrology (Turk Illeri) and history (including one on the history of Karabagh, called Garabaghname). Arabic Script Reforms As might be expected, it soon became clear that the Arabic alphabet was not a perfect fit for the Azeri language. For instance, medieval Azerbaijani writers found that they had to add a new letter to the Arabic alphabet to represent a nasal consonant sound found in medieval Azeri. The consonant sounded similar to the "ng" in the English word "ring". For example, the Azeri word for sea, "Daniz", was pronounced "Dangiz". "Alini yu!" (Wash your hands!) was pronounced "Alingi yu!" There was no letter for this "ng" sound in the Arabic alphabet, since it wasn't indigenous to either the Persian or Arabic language. The new letter became known as "saghir-nun" (little nun, "nun" being the original Arabic letter representing the "n" sound). Strangely, this sound was represented by adding three dots above the letter "kaf" - "k", not above "nun". You won't find the "saghir-nun" in manuscripts beyond the Turkic regions. Evidence is only found in Azerbaijan and neighboring regions. Poems by Nasimi (14th century) and Fuzuli (16th century) both use this letter. Even though this sound gradually disappeared from literary Azeri, the letter remained in the script up until the beginning of the 20th century. For example, you can find it Sabir's satire, Hop Hop Name (1922). Azeri also differs from Arabic and Persian in its use of the letter "ha" (the upside-down "e" in Azeri Latin, which represents the "a" sound in "fat cat"). In Persian and Arabic, this vowel sound is never written in the middle of a word - only at the end. But in medieval Azerbaijan, this letter was often used in the middle of words, even though this would have seemed like an error to most readers in Arabia or Persia. Therefore, there were three forms of the Arabic script spread throughout the region of Azerbaijan - Arabic, Persian and Turkic. Along with "saghir-nun" and the non-traditional use of "ha", the Azeri variant of Arabic included letters that had been invented by medieval Persians. These included the letters called "gafe-farse", "Zhe" (the first sound in the name "Jala", not "j" itself), "pe" and "chim". As a result the pure Arabic script contained 28 letters, Persian had 32, and Azerbaijani had 33 (all the Persian letters plus "saghir-nun"). All medieval Azeri texts were written in the slightly Arabic script modified for Persian. Of course, it was insufficient and inadequate and didn't meet the requirements of the Azeri language. For example, some sounds had duplicate letters (2 letters represent "t", 3 for "s" and 4 for "z"). And none of the short vowel sounds were represented at all (a, i, o, u). Mirza Fatali Akhundov (1812-1878) was one of the first Azerbaijanis to initiate any serious thought on reforming the Arabic script for Azeri. Other outstanding voices in the movement of reform were Mahammadagha Shahtakhtinski, who proposed various reforms between 1879 and 1902. Due to technical difficulties, none of these alphabets was implemented. In 1903, Shahtakhtinski founded the newspaper "Shargi Rus" (Russian East) primarily to discuss alphabet reform. In 1880, Chernyayevsky wrote a book about Arabic reform. That same year, Mirza Rida Khan Danish published a project introducing a Latin script called "Alphabet Rusdia." Between 1832 and 1920, at least 140 magazines and newspapers were published in Azeri using the Arabic script. It was an amazing number of publications for that period and illustrates how highly the written word was esteemed. Most of these newspapers and magazines are viewed as treasures at the Institute of Manuscripts and various other archives in Baku. They include the following: Azerbaijan (1918-1920), Achig Soz (1917-1918), Babayi-Amir (1915-1916), Bayraghi-Adalat (1917), Basirat (1915-1916), Baki Fahla Konfransinin Akhbari (1919), Bahlul (1907), Burkhani-Hagigat (1917), Dabistan, Valideyna Makhsus Varaga (1906), Gardash Komayi (1917), Fuyuzat, Gurtulush (1915-1920), Dan Yildizi, Dabistan (1907), Dilimizin islahi, Dirilik (1914, 1915), El Hayati (1918), Zanbur (1910-1919), Mazali, Ziya (1880-1883), Igbal (1913-1914), Irshad (1904), Yeni Fuyuzat (1910-1911), Yeni Irshad (1912), Yeni Igbal (1916) and Molla Nasraddin (almost the entire collection during its 25-year duration, 1906-1931). Also, some magazines were published in Azeri in Tbilisi (Georgia), such as Ziya and Akinchi. Burkhane-Hagigat was published in Yerevan (Armenia). The Azerbaijani magazines and newspapers that were published in the Arabic script (1920-1929) during the early Soviet Period were primarily devoted to various political and social problems related to work, culture, art and education. Written from a Soviet (Marxist-Leninist) ideological perspective, they were full of caustic criticism against Islam and the Arabic script. The State obviously wanted to set the stage for ridding the country of Arabic and introducing a new script - Latin. There are scores of Soviet-period editions written in Arabic archived in our Institute. They include Azerbaijan Hamkarlar Harakati (1926), Azarbaycan Ali Igtisad Shurasinin Akhbari (1922), Baki Shurasi Khabarlari (1928), Beshillik (1926), Bolshevik (1927), Gizil Baki (1925), Gizil Galam (1924), Gizil Yardim (1926), Gizil Ganja (1924), Gizil Talaba (1924) and Gizil Sharg (1923). Southern Azerbaijan We have quite a number of manuscripts and books in Azeri that were published in Southern Azerbaijan (now Iran) and written in the Arabic script. Among them are newspapers and magazines published in Tabriz during the national movement of the 1940s during the Soviet occupation and the government of Pishavari, as well as later. These include: Azerbaijan (published by the Azerbaijan Democratic Party) (1941, 1954-1955); Azad Millat (Independent Nation) (1946) and Vatan Yolunda (In the Name of Motherland) (1942). Azeri Latin (1929-1939) When Azerbaijan decided to switch to a Latin alphabet during the early Soviet period, many of the Arabic publications changed to the new script. The ones that continued to publish in Arabic were used by the Soviet government to issue propaganda bitterly criticizing Islam and the Arabic script. From the late 1920s onwards, there was a widespread campaign to destroy all Arabic texts, whether they related to religion, science, medicine or literature (See AI 7.3, Autumn 1999, "The Day They Burned Our Books" by Asaf Rustamov). A number of the periodicals published in the early Latin script are kept at our Institute. They include: Gizil Araz (1938), Gizil Shafag (1930), Adabiyyat Gazeti (1936), Adabiyyat Jabhasinda (1930), Zagafgaziya Bolsheviki (1931), Zarba (1932) and Ingilab ve Madaniyyat (1928-1933). These documents often emphasized that the transition to the Latin alphabet played a valuable role in the struggle against illiteracy in Azerbaijan. Transition to Cyrillic (1939) The transition to Cyrillic began in 1939, when the Stalinist repression was at its height. Apparently Stalin had not anticipated that Turkey would also adopt Latin and wanted to discourage any contact between Turkey and the Turkic Republics. During the Repression, tens of thousands of citizens, not just in Azerbaijan, but throughout the Soviet Union, were being arrested, jailed and either executed or sent to labor camps in Siberia. Keep in mind that the USSR was preparing itself for war against Germany at the time as well. Turkey was an ally of Germany in both World Wars. As a result, thousands of Azerbaijanis (who were categorized as Turks) were interred in prison from regions extending from the border of Turkey eastward to Central Asia. I haven't been able to find anything about a serious struggle against the transition to Cyrillic in Azerbaijan. Unfortunately, nobody at our Institute is especially engaged in the study of alphabet itself. However there are sources available at the Manuscript Institute that include both the early and the late variations of Cyrillic used in Azerbaijan. The official name of our people (Azeri Turks) as well as the alphabet (which was Latin and similar to the Turkish script) was changed. Two years earlier in 1937, most Azeri dissidents, as well as any bold and free-thinking individuals, had been executed or imprisoned. The surviving population became extremely fearful. Who would have dared to raise an objection against Stalin's decision to impose the Cyrillic script? And if they had, who would have dared to keep any records? _______ Medical Historian

Farid Alakbarov has been researching ancient manuscripts

at Baku's Institute of Manuscripts since 1986. He has written

several books about his studies of ancient medical texts, including

"The Comparative Analysis of Medicinal Herbs of the Middle

Ages and Contemporary Azerbaijan" and "Treatment Methods

Used in Medieval Azerbaijan." Farid has also written a book

in Azeri Latin called "Science in Tales," which introduces

concepts like DNA, symbiosis and photosynthesis in a fairy tale

format for children. |