|

Spring

2000 (8.1)

Editorial

Alphabet

& Language in Transition

by

Betty Blair, Editor

Nikos Kazantzakis (1885-1957),

the great modern Greek writer of "Zorba, the Greek",

was known to be a workaholic. For days on end, he would barely

break away from his desk. His friends would worry and warn him,

"Take good care of your body. Don't abuse it. It's the only

donkey that you have to carry your soul around on earth." Nikos Kazantzakis (1885-1957),

the great modern Greek writer of "Zorba, the Greek",

was known to be a workaholic. For days on end, he would barely

break away from his desk. His friends would worry and warn him,

"Take good care of your body. Don't abuse it. It's the only

donkey that you have to carry your soul around on earth."

In a sense, the same analogy can be made between language and

this creation that we call "alphabet" - the real workhorse

of culture. Alphabets carry the load of the written form of all

our discoveries, thoughts and beliefs. Alphabets connect us to

a world beyond our own physical presence, both in terms of history

and geography. And that's why we must respect these symbolic

systems and take good care of them.

Four Alphabet Changes

The trouble for Azerbaijan this past century is that the alphabet

- this beast of burden - has been changed four times mid-stream

and the nation still suffers immensely from the incredible loss

of this cultural treasury.

The first change came when Latin replaced Arabic - a script that

had been used for more than a millennium. The shift began in

1923 when Latin was declared the State language alongside Arabic.

By 1929, Soviets had banned Arabic and gone on ravaging book-burning

campaigns throughout the towns and villages of Azerbaijan and

the Central Asian Turkic-speaking states to scourge the alphabet

from the land along with anything associated with Islam.

In 1939, again the cultural burden was shifted. This time from

Latin to Cyrillic as Stalin became very concerned that Latin

might become the consolidating factor unifying all Soviet Turkic-speaking

nations and Turkey against himself. So he imposed Cyrillic. Finally

in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed and Azerbaijan gained

its independence, one of its first articulations of glee was

to give Cyrillic a kick and begin transferring the load back

onto Latin once more - exactly where it had been before Stalin

intervened 50 years earlier.

Orphaned Youth Orphaned Youth

None of these alphabet changes has truly been successful in terms

of enabling younger generations to access the knowledge acquired

by its older members in society. Each time the alphabet was changed,

the younger generation was left orphaned, alone on its own to

scrounge around as best it could in search of the repository

of national, cultural, and historical knowledge. For the most

part, the valued treasure just slipped off the back of the donkey

and plunged into the swiftly flowing stream of political and

economic expediency to disappear forever. Historians are likely

to write that these frequent alphabet changes are one of the

greatest tragedies that Azerbaijan experienced this past century.

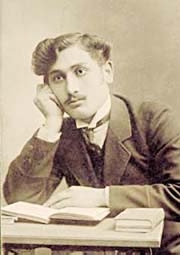

Photo: Formal studio portrait

in 1911 of Ismayil Mustafayev who is shown with books, emphasizing

how important the written word was valued and esteemed in society.

The official alphabet at the time was Arabic. Courtesy: Adila

Khanmirzayeva.

Intellectual resources could not be utilized to their fullest

extent because written records had either been destroyed, were

no longer "politically correct", or were simply unreadable

to younger generations. See "The Day They Burned Our Books" by the late Dr.

Asaf Rustamov in Autumn 1999 (AI 7.3, page 74).

Deliberate Choice

The decision to adopt Latin in 1923 seems to be the most deliberate

and calculated of all changes. Set in the context of religious

tradition, it was thoroughly discussed, unlike Cyrillic which

followed a few years later and was imposed by Stalin's regime.

Intellectuals blamed Arabic for the nation's backwardness and

lack of progress. They jealously eyed the rapid development and

industrialization that was taking place in Europe.

Latinists wanted an alphabet that would facilitate literacy and

accurately reflect the Azeri sound system as the Persian-modified

Arabic script had several shortcomings. Several letters represented

the same sounds (s, t, z); while other sounds were not represented

at all such as s( ), were critical to

determining meaning in the Azerbaijani language. ), were critical to

determining meaning in the Azerbaijani language.

It's rare to find Arabic script books in the Azerbaijan Republic

today except in museums. It's rarer still to find young people

who can read these texts despite the fact that this same script

is alive and vibrant in Iran today where an estimated 25 to 30

million Azerbaijanis live.

Of course, it can be argued that not many people were literate

in the Arabic alphabet back at the turn of last century and not

many books had been printed. But one should not forget the rare

treasures among those hand-written manuscripts particularly in

the medical field where the pharmaceutical powers of indigenous

plants had been so carefully documented. Much of that rare knowledge

went up in flames. It's a great loss, not only to Azerbaijan,

but to the entire world especially as modern medicine seeks to

unravel the mysteries of traditional medicine.

Cyrillic Imposed

Stalin imposed Cyrillic in 1939, at the height of what is known

as the Stalinist Repression. It was during the time when tens

of thousands of intellectuals throughout Azerbaijan and the Soviet

Union who were suspected of being critical of the regime's political

policies were arrested and either executed or sent into exile

in Siberia. Is there any wonder that Cyrillic met with so little

resistance? Azerbaijanis bowed their heads in submission, clinging

to the hope that adopting the alphabet that was created to express

the Russian language would not wreck havoc on the sound system

of Azeri.

Back to Latin

Nowadays, the donkey is again caught midstream as the transition

takes place between Cyrillic and Latin. Turbulent waters are

swirling around the treasured wealth once again. However, the

situation is quite different than on previous occasions. Compared

to earlier periods, there is an abundance of written material

produced during the 70 years of Soviet power that needs to be

converted to Azeri Latin. If younger generations are denied access

to these materials, the loss will be irreparable.

When the transition from Arabic to Latin was being considered

early last century, one advocate insisted that the cost to republish

all Arabic texts to Latin would be no greater than the cost of

a battleship - a sum that he felt was quite manageable.

Today, the situation is different. It doesn't take long for a

cash-strapped Azerbaijan to run out of battleships. One publishing

house director figured that if the transition were extremely

well planned (which he insists it hasn't been) that republishing

major works could be completed in 15 years.

But with the proliferation of Web sites on the Internet, who

can imagine what body of knowledge will be available to youth

of the international community these next 15 years while Azerbaijan

is just trying to catch up with itself? Time will not stand still.

Azerbaijan needs to catapult itself into the 21st century or

it will be left far behind.

Legendary Speed

Azerbaijan doesn't need a donkey right now; it needs a horse

at the speed of lightning - like the legendary Girat of Koroghlu

fame that always came to the rescue of his master, whisking him

away from danger. What many Azerbaijanis don't realize is that

Girat is alive and well and already exists in their midst in

the form of computers and associated technologies.

Unfortunately, many members of the older generation who are decision

makers don't really comprehend the power of computers. They have

not grown up using them nor had practical, hands-on experience.

Most of them view the computer as a mysterious sophisticated

electronic version of the typewriter which, of course, strips

it of its greatest capability - the ability to remember and store

information which can be made accessible at the push of a button

and to link it with a worldwide network via the Internet.

The problems we've discussed in this issue are like "déjà

vu" all over again. In 1993, Azerbaijan International dedicated

one of its earliest issues to the Alphabet transition and as

editor, I wrote my first article about the font problem, entitled

"The Upside-down

'e' - an Editor's Nightmare" (See AI 1:3, page 40). Well, seven years

have passed and the nightmare has only intensified. The main

culprit is that no standardization has taken place either in

regard to character assignment of Azeri fonts or the standardization

of keyboard layout. Standardization will take place by default,

sooner or later, but it could happen considerably faster and

with much less wasted energy if there were government support.

Young people stand to lose immensely from further delay. A generation

of young people weaned on the Latin script from the early primary

grades is now getting ready to enter the doors of the university.

And, for the most part, they are more poorly educated than their

parents and grandparents. Students who have followed the Azeri

track at school have had little access to books beyond a few

textbooks. In the university, they'll discover little to read

except old, out-dated texts in Cyrillic, as so few books are

available on these higher levels in Latin. What are kids to do?

The lack of intellectual challenge for this generation's youth

is an enormous problem with long-range consequences.

Azerbaijanis cannot rely on old print methods to solve this problem

of making Cyrillic texts available in Latin. It's far too expensive

and there just aren't enough battleships to trade in for cash.

Instead, they need to plunge into new technologies and carefully

strategize to make full use of the Internet. Let the Internet

become the beast of burden as it revolutionizes modern life and

the way we acquire information.

Entire books can now be downloaded from Web sites on computers

(See Project Gutenberg. Commercial ventures are developing new inventions

called electronic books (e-books), the size of a book itself,

which can be filled with scores of books at the same time. These

are the tools that Azerbaijan must use to solve these problems.

Azerbaijan must foster the creation of Web sites not only by

government institutions but by personal entrepreneurs to get

Cyrillic texts converted to Azeri and make them available in

every major field of endeavor from science and medicine to math,

history and music. We shouldn't be thinking in terms of hundreds

but rather tens of thousands.

Usually, our magazine is descriptive and our targeted audience

is foreigners who have had little chance to learn about Azerbaijan.

But this time, we hope our issue on Alphabet and Language Transition

can serve as a catalyst to empower Azerbaijanis who are deeply

concerned about this problem and who are pushing for action within

the Azeri community.

And so our admonition to Azerbaijan would be: Take care of that

donkey - the alphabet. Make sure the cultural load this time

is transferred to a speedy critter like Girat, that magical horse

of legendary and heroic strength so that it can carry the load

for generations to come. After all, it's the only means of

bearing up your soul on this fast-paced planet called Earth.

From Azerbaijan International (8.1) Spring 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Home

| About Azeri | Learn

Azeri | Contact us

|