|

September 1993

(1.3)

by Abulfazl

Bahadori

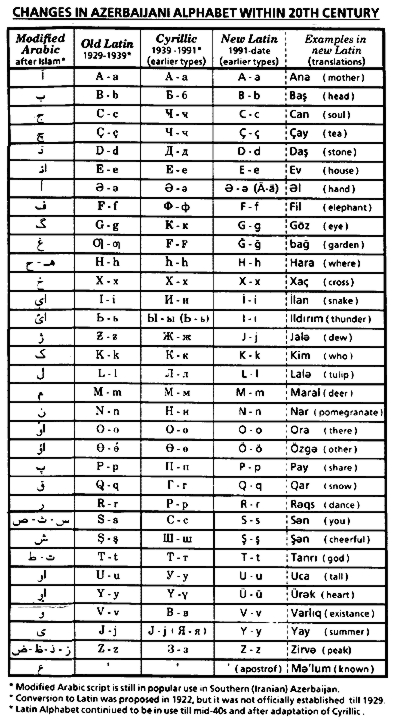

Conservatively speaking, the

Azerbaijani or Azeri alphabet to date has been altered four times--to

Arabic after the Islamic conquest; to Latin (1928-1938); to Cyrillic

(1939-1991) and to Latin again (1991 to present). On each occasion,

the motivation for change was political. However, if we consider

the replacement of a single letter in any of the phonetic alphabets

(Cyrillic or Latin), then the Azeri alphabet has been changed

at least ten times (Tables 2,3,4). Nor does this take into account

the pre-Islamic scripts used by the Turkic nations and other

ancestors of modern Azerbaijanis such as Caucasian Albanians.

If those are added, then the historical fgure would be raised

to twelve or more, depending on how far back one digs in search

of ancient scripts. (See Table 1 and Sample 1).

ISLAM-the First

Political Reason for

Changing the Alphabet

For many centuries after the

conquest of Islam, the only offcial written language in the conquered

lands, including Azerbaijan, was Arabic as the Islamic caliphate

had to create a linqua franca to unify their territory. When

these nations began using their own languages for reading and

writing, the Arabic alphabet was retained. The most valuable

contribution that the Arabic alphabet made for the Turkic tribes

and nations was to provide them with a more-or-less universal

script (the Arabic letters generally do not express all the vowel

sounds which is one of the most obvious differences between various

dialects and closely-related Turkic languages). Hence, this common

means of communication made the great poet and philosopher Fizuli

as much Turkish (Ottoman) as he was Azerbaijani or the great

thinker of Turkistan, Ali-Shir Navayi, as much understood in

Tabriz as in Bukhara.

On the other hand, since the Middle ages, it is precisely because

the Arabic script does not express the vowels that it was so

strongly criticized.1 However,

it wasn't until the 20th century that the Arabic alphabet was

totally replaced by another script.

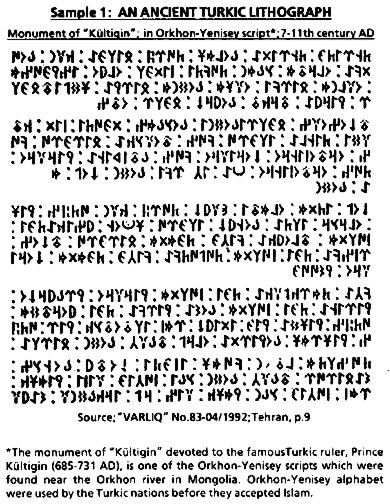

The Monument of "Kultigin" devoted to the famous

Turkic ruler, Prince Kultigin (685-731 AD) is one of the Orkhan-Yenisey

scripts which were found near the Orkhon river in Mongolia. Orkhon-Yenisey

alphabet was used by the Turkic nations before they accepted

Islam.

The frst attempts to alter the

Arabic script (1860-1870) were made by three individuals: Manif

Pasha, a scholar in the Turkish court; Malkom Khan, an Iranian

Armenian intellectual in the Russian Embassy in Tehran; and Akhunzadeh,

the great Azerbaijani thinker, writer, and dramatist, who was

the most active of all. All three were friends who wanted to

westernize Muslim society. Akhundzadeh, an atheist, pushed for

the reform to counter Islamic culture though none could ever

have dared to suggest adoption of the Latin alphabet as it would

have been blasphemous.2 Instead,

they pushed to eliminate the dots, express each vowel and make

the writing smoother and more continuous. Akhundzadeh believed

that one of the main reasons for "backwardness" among

the Muslim world laid in their style of education which was based

on the Arabic alphabet. As their reformist proposals were considered

political and anti-Islamic both by Istanbul and Tehran, they

were rejected. 3

Soviet Rule

Bans the Arabic Alphabet

After the death of Akhundzadeh

in 1878, the issue of "modernizing the alphabet" was

forgotten for a while, at least in offcial circles. After the

Revolution of 1917 and the fall of the Tsarist Empire, Azerbaijanis

established their own independent Republic which survived from

1918 until 1920 during which time the government continued publishing

all its offcial correspondence in the Arabic alphabet and the

issue of Latinization was offcially never raised.

In 1920, the Bolsheviks toppled the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan.

It was the "Soviet of Azerbaijan People's Commis-sars,"

set up by the Communists which in late 1921 organized the "New

Alphabet Committee." This was before any change had taken

place in Turkey regarding alphabet reform. In 1926 the frst Turkology

Conference was held in Baku which provided the linguistic and

scientifc justifcation for the Latin script which was adopted

fnally in 1929 ("Old Latin"-Table 2). For the Soviets,

Latinizing the alphabet was a means of severing the Muslim population

from their past and of preventing outside infuence. This process

was not confned to Azerbaijan but was carried out throughout

the entire Turkic Muslim population of Soviet Union.

In 1928, the Republic of Turkey replaced the traditional Arabic

alphabet with Latin. Although their motivations were similar

to the Soviets--centralization, westernization and disassociation

with the Islamic past--the modifcations to the script were signifcant

enough to make reading between the Latin scripts of the Soviet

Republics and Turkey diffcult. Whether this was intentional is

not clear.

Stalin Rules

Out Latin

Although Lenin had called Latinization

"the great revolution of the east," in 1939 the offcial

Literaturnaya Gazetta disagreed and wrote "the Latin script

does not provide all the necessary conditions for bringing the

other people (nationalities) closer to the great Russian people's

culture." Overnight, the Turkic populations of Soviet Union

were forced to convert to a new alphabet--Cyrillic. This decision

was so sudden that in Azerbaijan alone, certain characters were

changed several times (Table 4).

Conversion

to Cyrillic was carried out with two main goals: Russifcation

and isolation between Turkic nations. The second goal was achieved

by using different Cyrillic characters for the same sounds in

various Turkic languages; for example, the symbol "o"

was used in Uzbek for the same sound that appeared as an "a"

in Azeri, etc. The variety was suffciently complex so that ordinary

people of each nationality were not able to communicate in writing

with each other. Conversion

to Cyrillic was carried out with two main goals: Russifcation

and isolation between Turkic nations. The second goal was achieved

by using different Cyrillic characters for the same sounds in

various Turkic languages; for example, the symbol "o"

was used in Uzbek for the same sound that appeared as an "a"

in Azeri, etc. The variety was suffciently complex so that ordinary

people of each nationality were not able to communicate in writing

with each other.

An illustration of the evidence

of alphabet changes in Azerbaijan even on grave markers - here

in Arabic and Cyrillic. (Sufi Hamid Cemeteryone hour south of

Baku). Photo: Farid Mamedov

With Glasnost

came Alphabetical Perestroika 4

In 1985 with Gorbachev's nomination

as the new leader of the Soviet Union, the new policy of Glasnost

was announced. The frst signs of this new political openness

in Azerbaijan became evident by the enormous number of articles

in Azeri newspapers criticizing the colonialist nature of the

Cyrillic alphabet and the need to revive the old alphabet (Arabic).

This movement was led by the famous poet and writer, Bakhtiyar

Vahabzade, who in his long dramatic poem, "Iki Qorkhu"

(Two Fears) describes how Stalin frst used the Latin and then

the Cyrillic alphabet to separate Azerbaijan from its thousand

year old literature and southern brothers and sisters. Other

pro-traditional alphabet articles followed.5

Ziya Buniadov, a famous Azerbaijani scholar, was the frst to

call for a return to the Latin alphabet in July 1989.6 The

issue soon divided Azerbaijani intellectuals into pro-Latinists

and pro-Arabists. Heated discussions extended beyond geographical

boundaries into Iran and Turkey and took on a political entity

of their own. The days of Glasnost were over and the days of

the "Great Game"7 made

the alphabet yet again a victim of political competition and

purges.

The "Great

Game" and the Azeri Alphabet

The alphabet was the main ingredient

in the boiling pot of Turkish-Iranian politics. While the Latin

alphabet came to symbolize a propensity for the West, secularism,

and pro-Turkism; the Arabic (Koranic) alphabet was clearly associated

with the Islamic Republic of Iran and all its religious ramifcations.

Each competitor used different tactics to promote their own script.

Iran began increasing the number of publications available to

their own Azerbaijani populations. (Publication in Azeri had

been forbidden in Iran during the Pahlavi era from 1925-79) except

during the brief period from 1941 to 1946 when the country was

occupied by Allied forces.8

Many Azeri publications of the Revolution (1979-81) did not survive

under Islamic rule. In 1989, there was only one single Azeri

publication, Varliq, produced quarterly, half in Persian, half

in Azeri from the private resources of Dr. Javad Heyat. Varliq

only had a circulation of 2,000 despite the fact that more than

20 million Azerbaijanis lived in Iran. However the Iranian government

suddenly started devoting pages for Azeri in its offcial papers;

even the publication of Azeri books was somehow encouraged.9 Often

these papers concerned Northern Azer-baijanis more than Iranian

Azerbaijanis. A typical article would promote the Arabic alphabet

reminding the reader that the revival of Islam in Azerbaijan

demanded the revival of the Arabic alphabet.10

The most convincing and scientifc of these articles, however,

was published in Varliq by Dr. Abbas-Ali Javadi in 1369-1370

(1992).

In any case, northern Azerbaijani intellectuals argued that they

did not have a role model for the Arabic alphabet as Iranian

Azerbaijan did not provide them with a strong literary basis

for revival of the Arabic alphabet. The monthly Odlar Yurdu published

in Baku went so far as to argue that if the Iranian government

established Azerbajani schools where Azeri would be taught in

Arabic alphabet, then the North would welcome this by adopting

the Arabic alphabet instead of Latin. In itself, this was a very

political argument. It was like saying, "You have no right

to tell us what to do when your own Azeris don't even have a

single school in their own mother tongue."

This, along with various other reasons, including the lack of

expertise with the Arabic alphabet and its more tedious spelling

and writing techniques made the Turkish position for the Latin

script stronger. Turkey busily organized many linguistic seminars

and conferences on the Turkic alphabet. The most well known conference,

"The Common Alphabet of the Turkic Nations," was held

in Ankara in October of 1990 and organized by the Turkish Language

History Organization (Türkiye Dil Tarik Kurumu). In many

of these seminars and conferences, the arguments set forth were

extremely political: "A common alphabet is essential for

bringing together all the Turks of the world." In other

words, that which the Arabic alphabet had already done for many

centuries was now expected from Latin. The phonetic nature of

Latin made it too diffcult to hide the differences between them

as had been done with Arabic. This created another question of

what would happen to all the sounds which existed in the Turkic

languages other than those that existed in the Turkish language?

The radical answer was "get rid of them, make them sound

just like Turkish."

As one of the participants of the First International Congress

of Azerbaijan Turkish Associations (Istanbul, November 1990),

I was surprised that one of the leaders of Motherland (Anaveten)

party gave a "speech" basically declaring, "Your

alphabet must be exactly the same as ours." That a major

Turkish party leader was asking Azerbaijanis to copy the Turkish

Latin made the issue of alphabet so political it was hard to

believe that there was any other motivation behind it.

It could be argued that Turkey won the "Great Game"

of the alphabet. In May of 1990, the Republic Supreme Soviet

of Azerbaijan established a commission to work on the Latinization

20 and on December 25, 1991, the National Council of the Republic

of Azerbaijan offcially replaced the Cyrillic script with a modifed

Latin alphabet (See table 2)

But the Latin alphabet which the Azerbaijanis adopted was not

identical to the Turkish script. The new Azeri Latin now has

three letters which do not exist in Turkish Latin - x (kh sound),

upside down "e" (ae sound in "fat cat") and

q, which express sounds particular to the Azeri language which

do not exist in Turkish. Initially, a two-dotted (ä) was

designed for expressing the vowel sound in the English word,

"and". The idea was to make it look as similar to Turkish

and European alphabet as possible as well as to be able to use

foreign typewriters and read-made software. It must also be mentioned

that one of the criticisms against using the Arabic script was

its cumbersome use of dots which made writing so tedious. But,

because this sound is so frequent in Azeri, and the dots so cumbersome,

six months later, they reverted to the up-side down 'e' - a symbol

that had become very familiar to their eye as it had been used

both in the early Latin alphabet in 1928 and had even survived

Cyrillization.

Conclusion

Changing the alphabet so many

times in Azerbaijan has had severe consequences on the accumulative

wealth of knowledge and culture of the nation. It has hindered

continuity of the literary development, isolating the people

from centuries of knowledge, cultural insight and human wisdom.

It has erected intellectual barriers between generations. Children

often can't read their parents writing much less that of their

grandparents. And in some cases, brothers and sisters have even

experienced this separation and isolation from one another.

Alphabet change has created an incredible fnancial strain on

the society. Who pays for all the street signs and government

documents that must be transliterated much less the thousands

of books which should be republished?

At different times in its history, alphabet changes have served

to isolate Northern Azerbaijan from Southern Azerbaijan. If the

Araz river was the "natural" border between the two

Azerbaijanis and if the barbed wires emphasized physical separation;

then alphabet differences created a third boundary - an invisible

cultural one.

It has served to isolate Azerbaijan from related Turkic-speaking

peoples and from the West. But, perhaps, the greatest tragedy

to what is nearly a century old process is that if alphabet change

is carried out solely, or even, partially, for political purposes,

the damage can be catastrophic, as future purges by the ruling

politics will again and again make the "defenseless"

alphabet--its victim.

Footnotes

1 Abu Reyhan Biruni has emphasized the necessity

of using "E'rab" signs for vowels) in the Arabic script

in his book, Al sidle--on Seeds and Fruits--in Arabic.

2 Algar,

Hamid. Malkum Khan, Akhundzadeh and the Proposed Reform of the

Arabic Alphabet, Middle Eastern Studies. 5, 1969.

3 Algar

Hamid. 1969. Religions and State in Iran, 1785-1906: The Qajar

Period. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

4 Glasnost--"political

openness" and Peristroika--"restructuring" were

two terms introduced by Gorbachev and which soon became part

of the international vocabulary. In Azeri, they were called ashkarliq

and yeniden qurma..

5 Abbas-Ali

Javadi. 1990. Alphabet Changes. Varliq. Winter (1369, pp. 24-29;

Summer (1370) pp. 88-96; Autumns (1370) pp. 91-102.

6 Audrey

L. Alstadt. 1992. The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity under

the Russian Rule. Hoover Institution Press. Stanford University,

Stanford, CA, p. 209.

7 The

"Great Game" was a term used to refer to the political

competition in the Middle East between Russian and Britain during

the 19th century. Recently many journalists have used it to refer

to the competition between Iran and Turkey over the former Soviet

republics.

8 Yarshater,

Ehsan, Ed., 1992 Encyclopaedia Iranica. Javadi, H. and K. Burrill

in "Azeri Literature in Iran." Routledge & Kegan

Paul: London. p. 251.

9 Offcial

papers like Kayhane Havayi and Etela'at printed a few pages of

Azeri in the Arabic alphabet. In Tabriz the new Azeri papers

like Sahand and Ark have been published and Islami Birlik even

includes a few pages in the Cyrillic alphabet.

10 There

are more or less similar articles on this topic in almost every

issue of the journal, Yol, between 1990-1992.

From

Azerbaijan International (1.3) September 1993

© Azerbaijan International 1993. All rights reserved.

Home

Home | About

Azeri | Learn Azeri

| Contact us

|