|

Autumn 2000 (8.3)

Silk Road

The Origin

of the Mulberry Trees

by

Farid Alakbarov and Iskandar Aliyev

Above: Shaki, a city in northwestern

Azerbaijan, was a large center for silk production. Since the

collapse of the Soviet Union, production has been greatly reduced.

Photo: Blair

Fresh

mulberries are so fragile and perishable that they have not yet

been grown commercially in the United States, making them very

rare and sought after - especially in California. Restaurant

chefs have been known to line up for hours at outdoor markets

to buy these fashionable berries at $10 to $15 a pound. In the

Los Angeles area, some Iranian immigrants have even resorted

to planting their own mulberry orchards so that they will have

easy access to their favorite fruit. But in Baku, mulberry trees

can be found in parks and lining streets and boulevards. It's

one of the favorite fruits.

This sweet, juicy berry is by no means a newcomer to Azerbaijan.

By the Middle Ages, there were already many different types of

mulberries in the region, including varieties like aghtut, khartut,

chardagli, shahtut, bidana, kharji (seedless), Shirvani, Tehrani

and garatut. There are three main species of mulberries - white,

red and black - all of them widely cultivated throughout Azerbaijan.

The white mulberry in particular grows in the forests stretched

along the Kur, Araz and Samur rivers.

_____

To pick mulberries, a person - often a young boy - climbs the

tree and shakes the branches, causing the fruit to drop onto

a cloth or plastic sheet below. The berries are very delicate

and therefore need to be handled carefully so that they don't

break open - the stain won't wash out.

Azerbaijanis don't grow mulberry trees just for their fruit,

however. In the summer, residents in the villages around Baku

used to sit and drink tea or play nard (backgammon) in the cool

shade of mulberry trees. There's a square in the Old City (Ichari

Shahar) that takes its name after the tree. Even a song has been

written about the mulberry tree.

Today, mulberry trees

(most frequently those bearing black fruit) line the streets

of Baku and lend shade to courtyards. In the countryside, mulberry

trees are often found in orchards and courtyards, along with

a variety of other fruit trees like cherry, fig, pomegranate,

apricot, apple and pear. Today, mulberry trees

(most frequently those bearing black fruit) line the streets

of Baku and lend shade to courtyards. In the countryside, mulberry

trees are often found in orchards and courtyards, along with

a variety of other fruit trees like cherry, fig, pomegranate,

apricot, apple and pear.

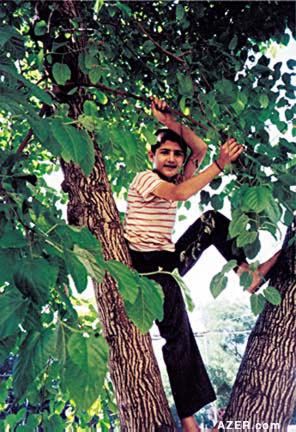

Left: Mulberry season in

June as evidenced by the tell-tale purple stains on tree-climbing

youth. Photo: Blair

Originally, male (fruitless) mulberry trees were planted along

the streets and in the parks of Baku in order to provide shade

and decoration. But somehow it happened that some female trees

got planted as well. When their fruit becomes ripe each June,

it tends to drop to the ground and stain the sidewalks. That's

how you know it's mulberry season in Azerbaijan - that and kids'

faces stained with the dark purple juice.

Mulberries as Medicine

When mulberries are no longer in season, Azerbaijanis still enjoy

eating them in the form of mulberry syrup concentrates known

as "doshab" and "bakmaz". To make the syrup,

mulberry juice is boiled until it has a consistency that's much

like honey.

While this syrup makes a tasty sweet, it is also used as a medicine

to protect against diseases of the liver, gall bladder and heart.

To treat gallbladder infections, one is supposed to drink 2 tablespoons

of bakmaz dissolved in half a glass of water, then lie down in

bed on his or her right side. The treatment should be taken on

an empty stomach, half an hour before breakfast.

Bakmaz is used to treat sore throats as well. In 1836, Abbasgulu

Agha Bakikhanov, a famous scholar and son of Baku's last khan,

sent several bottles of bakmaz to his friend Dmitry Bibikov,

who headed the Department of Foreign Trade in Russia. Bakikhanov

wrote: "Dear Sir...According to my promise, I am sending

you a box of bottled syrups. Two of them are of mulberry, one

of quince, and the smaller one, sour plum (goyam)...

Mulberry syrup is good for use against throat pain. Apply the

syrup on the throat externally, cover with a cloth and keep this

compress on all night. You can also drink the mulberry syrup

a little bit at a time or mix it with soup. Quince syrup is good

for a weak stomach and strengthens it, whereas sour plum syrup

adds a cooling sourness to foods. If you would like, I could

send you more syrups."

Tut araghi, a potent liqueur (vodka) made from mulberry juice,

is another mulberry product that's very popular - not only Azerbaijan,

but also in Georgia and Armenia. It's one of the national Azerbaijani

versions of vodka. Another type is zogal araghi (vodka made of

cornelian cherry). Some people believe that small doses of these

drinks protect against diseases of the stomach and heart.

Food for Silkworms

Azerbaijanis have found many uses for other parts of the mulberry

tree, such as boiling the roots to make black dye and making

the wood into furniture and musical instruments. But by far,

the mulberry tree's most significant impact in Azerbaijan has

been on its silk industry. Leaves from white mulberry trees are

used to feed silkworms in order to make the product that gave

the Silk Road its name.

Azerbaijan's Shirvan region started becoming known for its silk

industry as early as the 9th century. By the 11th and 12th centuries,

the silk produced in Shirvan was already famous throughout Russia

and Western Europe. Silk cloth was exported to Italy by Venetian

and Genoese merchants who maintained commercial offices along

the shores of the Caspian.

In 1293, Marco Polo himself wrote that the Genoese ships were

engaged in the silk business in the Caspian region. He writes:

"Shirvan dwellers make golden and silk clothes. You can't

find such beautiful things anywhere else."

Above: A typical family scene

in the early 1960s when neighbors would gather to help each other

clean silkworm cocoons in preparation for silk production in

Balakan. Courtesy: Sadikhova

Similarly, Adam Oleari, a traveler who visited Shirvan in the

17th century, wrote that Azerbaijan produced up to 2.5 million

kg of silk cloth each year. In the town of Shaki alone, 14,000

families were engaged in silkworm breeding and produced approximately

15,000 poods (240 tons) of raw silk each year. Part of this silk

thread was exported; the other part was woven and dyed in local

factories.

During the Soviet period, leaders like Brezhnev wanted to substitute

cotton for the silk industry in Azerbaijan. Even so, Shaki kept

its thriving silk industry, employing thousands of people up

until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Mass Planting

In 1961 Azerbaijan's Cabinet of Ministers issued a decree to

encourage silkworm raising. According to a series of five-year

plans, 3.8 million new mulberry trees were to be planted each

year, all over the Republic.

The decree encompassed 42 different regions of Azerbaijan, including

the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, Aghdam, Aghjabadi, Astara,

Balakan, Beylagan, Gakh, Gubadli, Gabala, Gazakh, Zangalan, Masalli,

Saatli, Sabirabad, Tovuz, Ujar, Khanlar, Khachmaz, Jalilabad

and Shaki. For instance, in Aghdam, where growing conditions

were good and there was already a considerable amount of agriculture

going on, 324,600 mulberry trees were planted.

To distribute seeds for these new mulberry trees, the Ministry

of Agriculture organized a Seed Center. Before the Center was

organized, mulberry seeds had to be imported from Uzbekistan,

Turkmenistan, Russia, Ukraine and other Soviet republics.

Above:

The traditional

way to gather mulberries is for someone to climb up the tree

and shake the branches so the mulberries fall on a sheet below.

Courtesy: National Archives of Photo and Cinema

These seeds were then distributed to families living in the areas

where the silk industry was to be developed. The families also

received tiny silkworm eggs, which were kept in matchboxes.

It's not an easy task to look after silkworms. You have to put

the silkworm eggs on mulberry twigs with leaves. The silkworms

eat the leaves and then spin a large cocoon as they encircle

themselves with silk. Once the worms produce enough raw silk,

the cocoon has to be removed and cleaned. Families were paid

by the kilo for the cocoons that were produced.

Silkworm raising was especially prominent in the regions of Balakan

and Zagatala, up in the mountains close to the Georgian border.

The families who participated had to have enough room for mulberry

trees in their garden as well as time for raising the silkworms.

The white mulberry (Morus alba) was their primary food. Sometimes

neighbors would gather together to help clean the cocoons.

Mulberry trees were also planted in regions where people didn't

raise silkworms, in order to help produce mulberry leaves for

the regions where there was a silk industry.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, silk production in

Azerbaijan shrank to next to nothing, though it is still quite

a thriving industry in Kazakhstan. Instead of planting millions

of mulberry trees each year, the Azerbaijani government only

plants a few thousand.

In the town of Shaki, the silk factory no longer hums with the

activity it once did. Who knows whether the industry will ever

be revived to the extent it was in the past. In the meantime,

the trees are living proof of an era that once thrived along

the famous Silk Route that crisscrossed Asia and Europe for centuries.

Farid Alakbarov provided the historical background of the medieval period

for this article while Iskandar Aliyev described the Soviet

period of the 1960s when Baku planted so many of the mulberry

trees that line its streets today. The Los Angeles Times

was our source for ideas relating to the contemporary craving

of Southern Californians for this delicacy. See "Fruits

of California: Berry Frenzy: Mulberries are the Fruit People

Go Nuts For" by David Karp, July 19, 2000, page H1. Staff

members Farida Sadikhova and Arzu Aghayeva also

contributed to this article.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.3) Autumn 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

|