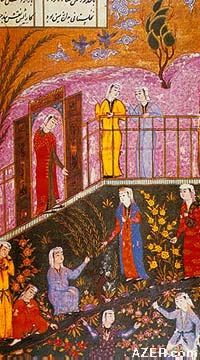

Scents That Heal Aromatherapy in Ancient Azerbaijani Medicine by Dr. Farid Alakbarov Is your life tense and stressful? Maybe chamomile can help. Need to clear out some of that mental "fog" and regain your focus? Try peppermint. Feeling frustrated, irritable or anxious? Perhaps lavender is the solution. Claims like these are currently being made by practitioners of aromatherapy, a type of alternative medicine that is gaining popularity in the United States and Europe. Aromatherapists believe that flowers and herbs have value beyond their wonderful smells-perhaps these plants even have the power to heal. The practice of aromatherapy is believed to date back several millennia to the Egyptians and Babylonians, who often took baths with aromatic herbs and other substances for hygienic and medicinal purposes. For instance, Egyptian queen Cleopatra was known to bathe regularly with rose petals. In Azerbaijan as well, aromatherapy was once considered to be part of mainstream medicine. Medieval Azerbaijani doctors regularly prescribed essential oils and other fragrances for their patients. For example, a bath that smelled of roses - such as Cleopatra used to take - would have been prescribed for someone who was feeling melancholic or who had a headache.  _____ What is aromatherapy? Today, this term usually refers to treatment with essential oils. These fragrant extracts come from flowers, fruits and herbs - such as rose, violet, thyme, lavender and marjoram - and are usually breathed in or applied to the skin. Although the term "aromatherapy" was only coined in 1937 by René-Mauricé Gattefossé, a French cosmetic chemist, the technique itself is thousands of years old. Ancient Beliefs In the ancient kingdoms of Manna (9th-7th centuries BC) and Atropatena (4th-1st centuries BC) - now situated in Southern Azerbaijan (Iran) - people believed that they had to be clean and beautiful in order to attain a higher spirituality. For these purposes, ancient Azerbaijanis used aromatic oils such as frankincense, myrrh, galbanum, rosemary, hyssop, cassia, cinnamon and spikenard. Some fragrant herbs and trees served a religious purpose. For example, the cypress, with its fragrant needles, was known as the tree of the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster). The dispersion of oils was also thought to purify the air and provide protection from evil spirits. According to ancient Turkic beliefs, all fragrant flowers were created by Tangry, the Supreme God of the Blue Sky. The Goddess of Grasses and Trees, Oleng, was his wife. Oleng was also considered to be the patroness of physicians. Each year, at the beginning of spring, the Turkic peoples held solemn festivals in honor of this goddess and burned fragrant herbs such as wormwood. Ancient Turkic legends tell that the souls of all children arise inside flowers and are then moved to their mothers' bodies. In a 7th-century legend, the elder named Gorgud says: "I was created inside a flower...moved to my mother's body, and born with the assistance of the gray-eyed Angel." Azerbaijanis treated diseases and injuries with aromatic substances. One scene describing such an occasion comes from the ancient Azerbaijani epic "Dada Gorgud" (Grandfather Gorgud), a compilation of legends that were set down in writing during the 11th century but contain stories that can be traced back to the 6th and 7th centuries. One of the scenes depicts how fragrant flowers were used to heal a lad who had been wounded: "Forty shapely girls ran, gathered flowers from the mountains, mixed them with mother's milk, rubbed this mixture on the wounds of the youth and left him with the healers." The flowers may have been spearmint and chamomile, which are known to have antiseptic and healing properties. Aromatic plants weren't just for healing. For instance, as far back as the 4th century AD, the people in Caucasian Albania (now northern Azerbaijan) used the herb thyme as both a tonic and an aphrodisiac.  After Islamic invaders conquered the region in the 7th century, Azerbaijanis began studying the chemical properties of essential oils. They learned from the experience of Muslim alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan (702-765) and other scholars who had helped to develop and refine the distillation process. In those times, Azerbaijanis could easily have extracted rose oil and prepared rose water, substances that were very popular throughout the entire East. Other essential oils used by medieval Azerbaijanis were fennel, melissa (lemon balm), spearmint, nutmeg, dill, chamomile, cinnamon, lime, orange, bergamot, lemon, myrrh, coriander, black cumin, tarragon, birch, cedarwood, cypress and myrtle. According to existing Azerbaijani manuscripts, at least 60 plant species were used in aromatherapy at the time. Unlike today, even aromatic animal species were used. Our documents identify eight of them. By studying essential oils, medieval Azerbaijani doctors were able to expand their understanding of aromatherapy and its ability to cure disease. Specific oils were used to treat certain ailments. For instance, basil oil was believed to relax the muscles and have a calming effect. As an ointment, it could heal wounds, cuts and sores. Basil and camphor mixed with flour was used against scorpion bites, and bergamot root was known to alleviate insect bites and act as a repellent. According to the poets Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1203) and Mahammad Fuzuli (1495-1556), rose oil was used as a remedy for headaches and as a topical antiseptic. Mahammad Yusif Shirvani (18th century) recommended an unguent of cumin for sword wounds. Though the concept of antibiotics was not known at the time, physicians did use ointments of cumin, honey and raw onion juice as topical antiseptics. We know that juniper oil was also used as an antiseptic because Haji Suleyman Iravani, a 17th-century Azerbaijani physician, recommends using ointment from juniper cones to heal wounds. Cypress was used as a strong diuretic for treating urinary disease. And for a person with a cold or a stuffy nose, doctors recommended inhaling the vapors from an infusion of thyme, peppermint or spearmint. Luxury Treatments Not everyone could afford these treatments. While substances like violet oil and rose water were fairly inexpensive, imported essential oils were quite costly and only available to the wealthy. Rich people liked to dab themselves with aromatic ointments, substances that also functioned as a form of currency. Kings would barter and buy land, gold, slaves and wives with their crudely extracted oils. Tenth-century writer Abu Ali Tanuhi observes that shahs and sultans possessed hundreds of jars of rare aromatic ointments in their treasure houses. Some of the ointments - which were worth their weight in gold - were brought from India, Egypt and Byzantium. Tanuhi writes of a miserly ruler who opened his jars, looked at his aromatic ointments with pride, then closed them again, explaining: "I can't bring myself to touch these treasures." Animal substances like musk, castor and ambergris were particularly expensive, as they had to be imported from China, Russia, the Persian Gulf and India. Not only were these fragrances supposed to attract the female sex; they were also believed to have therapeutic properties. A dab of ambergris - a gray, waxy substance from the intestinal canals of sperm whales - would strengthen the brain and heart, believed 17th-century physician Hasan ibn Riza Shirvani. This substance is often found floating in tropical seas; to reach Azerbaijan, it had to be imported from the coastal regions of the Indian and Pacific oceans. The scent of musk, it was believed, would strengthen the heart and nerves and help to get rid of melancholy. To alleviate a headache, musk was mixed with saffron; a single drop on one nostril would be sufficient. Castor, a substance secreted by male beavers to attract mates, often served as a substitute for musk. One or two drops of castor applied to the face and arms would make a person more appealing, it was believed. In 1311, Kabir Khoyi wrote that a bandage with a few drops of castor was good for treating headaches. Beverages containing castor and vinegar were also used to treat abdominal pain. Fourteenth-century Azerbaijani scholar Yusif ibn Ismail Khoyi describes eight different methods for administering aromatherapy: (1) Use a pillow filled with medicinal plants. (2) Carry a small pouch filled with dried medicinal plants. (3) Inhale the boiling decoctions of medicinal herbs. (4) Inhale the scent of flowers in special gardens. (5) Hang bunches of healing grasses inside the house. (6) Breathe the odor of burned medicinal plants. (7) Use an aromatic ointment. (8) Take an aromatic bath. The Fragrant Bath Modern science has proved that bathing can release muscle tension, dilate blood vessels and slow the heart rate. Baths that contain essential oils are also beneficial. Aromatic baths treat many diseases, eliminate melancholy and nourish the skin and hair. The earliest information about therapy with bathing and aromatic herbs is documented in the Indian Vedas in 1500 BC. Of the various types of aromatherapy, aromatic ointments and baths were the most widely used in medieval times. In Eastern bathhouses, fragrant substances were often added directly to the bathwater. For example, in the 17th century, Mu'min wrote that bathing in a decoction of pine needles was good for diseases of the uterus and rectum. Khoyi believed that laurel baths were effective against urinary disease. Another method was to apply aromatic ointments to patients' bodies before or after bathing. For example, for a person who had bladder stones, a doctor would have recommended a post-bath massage with an ointment made of pine pitch, euphorbia juice and bdellium (a gum resin similar to myrrh). Aromatic substances could also be breathed in during the bath. Usually, the patient would place himself near the fragrant fruit or perfume, such as camphor or musk. It was believed that these aromatic substances would strengthen the heart and act as a sedative. The temperature of the water and the duration of the bath were also important to the treatment. "[Hot] water in a bath should not cover the patient's chest or heart," Ibn Sina (Avicenna) tells. Patients were supposed to bathe while the skin continued to redden and swell. They were advised to stop bathing once the skin turned pale. According to Azerbaijani folk medicine, after a hot bath or nap, one should apply rose, narcissus or violet essential oils to the face and body. Eastern women especially liked these oils because they made the skin silky and soft. Pine Needles Some Azerbaijanis use pine branches to prepare an extraction for bathing, a substance that is supposed to strengthen the nervous system. The essential oil from pine is condensed to a thick syrup, then dried and pressed into tablets. Rosemary In Azerbaijan, people with low blood pressure are advised to take a bath with rosemary. It is believed that this fragrant plant stimulates the circulation and serves as a tonic. The recipe has even been documented. To prepare the solution, pour 4 cups of boiling water into a pot containing 5 tablespoons of rosemary leaves, cover, and let steep for 30 minutes. Strain the infusion and add to warm bathwater. The optimal duration for such a procedure is half an hour. Lavender According to Azerbaijani folk medicine, bathing in a lavender decoction has anti-spasmodic and calming effects and is used for neurasthenia and tachycardia (rapid heartbeat). Marjoram Taking a bath with a marjoram decoction is good for flatulence and nervousness and has a diuretic effect, Azerbaijani folk healers say. Melissa According to Azerbaijani folk medicine, bathing in a melissa (lemon balm) decoction is good for heart disease, relief of tachycardia and lowering of the blood pressure. The bathwater must be warm, but not hot. The Power of Smell Medieval Azerbaijani physicians believed that the smells of these aromatic substances could help cure ailments. Scholars proposed a type of therapy that may be called "therapeutic use of flower gardens." Medieval Eastern rulers and nobility were advised to spend their leisure time in flowering gardens, for their own treatment and relaxation. If they inhaled the fragrances of flowers, it was believed that they would relax and be cured. Considering that medieval Azerbaijani doctors were working without the advances of modern scientific medicine, aromatherapy was a fairly ingenious way to treat patients with natural substances that were readily available. For instance, physicians had figured out how to use frankincense and myrrh as natural antiseptics. Herbs like spearmint and chamomile were also known to have antiseptic and healing properties. Today, scientists know that these fragrant herbs contain essential oils that are able to kill microbes and clean and heal wounds. Forgotten Knowledge Unfortunately, the use of aromatherapy is not widespread in Azerbaijan today - in fact, many Azerbaijani doctors have never even heard of the term. These practices are only followed on a small scale by folk healers, who rely on herbs like thyme, rose and lemon balm. A great many of the manuscripts related to aromatherapy that survived from the Middle Ages were destroyed during this past century. After the Bolsheviks captured Baku in 1920 and established the Soviet Union, Azerbaijanis were forced to forget their historical roots, religions, traditions and beliefs. Purge of Arabic Script The Bolsheviks set out to completely destroy the "Old World of Violence" and build up what they considered to be a more idealistic world of their own. As the Soviets were eager to stamp out all Islamic influence, they carried out book-burning campaigns. But it wasn't just the Koran and religious manuscripts that fell victim to such a policy. Manuscripts containing medical and scientific observations that were written in the Arabic script were destroyed, too. [See articles by the late Dr. Asaf Rustamov: (1) "Purging Arabic Script: Loss of Medical Knowledge" (AI 3.4), Winter 1995. Also (2) "Just for Kids: The Day They Burned Our Books" (AI 7.3), Autumn 1999]. Stalin wanted all things in the Soviet Union to be new - new Soviet medicine, new Soviet science, new Soviet culture, new Soviet technology and industry, new Soviet intellectuals and new Soviet people. He himself wrote extensive volumes about these new fields; during his lifetime (up until 1953), they were revered like bibles for Soviet ideology. Ancient medical books were burned, traditional herbal pharmaceutical stores were closed and folk healers were arrested, imprisoned or sometimes even executed. Ancient books about medicinal plants were not valued. All things related to national traditions were considered outdated, foolish and harmful from an ideological point of view. It may seem strange to us today, but under Stalin's regime, anyone who dared to read ancient medical books written in Arabic could have been arrested as a spy. After Stalin's death, Soviet laws were still very strict against folk healers. Even during Brezhnev's era, which was relatively mild and peaceful, folk healers were considered charlatans. It was strictly forbidden to heal with the help of ancient recipes. Only Soviet-educated physicians could treat patients, and they were not allowed to use aromatherapy and other traditional treatments. If a doctor used traditional medicine illegally, he could have been convicted by a court and deprived of his medical diploma, or even imprisoned for several years as a quack. Some of the older folk healers in remote villages continued to heal with aromatic plants illegally and secretly. Sometimes, Soviet authorities didn't pay attention to these people and considered them to be insignificant. Thanks to these healers, some elements of Azerbaijan folk medicine have survived. But for the most part, the heritage has been lost. How could the tradition of aromatherapy survive completely, if throughout the 70 years of Soviet domination, the books in this field were forbidden, the folk healers were persecuted and the idea itself was considered non-scientific, outdated and foolish? Alphabet Change Dr. Farid

Alakbarov

holds a doctoral degree in Historical Sciences and a Candidate

of Sciences degree in Biology. His most recent book, "One

Thousand and One Secrets of the East", documents his research

of the fascinating field of Azerbaijan's medieval medical manuscripts.

The book was published in Baku, 2001 (in Russian). Dr. Alakbarov

has written several articles for Azerbaijan International magazine

starting in 1997, especially concerning medieval medical manuscripts

in the Arabic script. SEARCH at AZER.com. Contact him at alakbarov_farid@hotmail.com. |