|

Autumn 2002 (10.3)

Baku's Old City

Memories

of How It Used to Be

by Farid Alakbarov

Baku's "Ichari Shahar" (literally,

Inner City), often referred to by foreigners as the "Old

City", is a unique architectural preserve that differs considerably

from the other ancient cities of Azerbaijan. Ichari Shahar [pronounced

ee-char-EE sha-HAR] has many fascinating architectural monuments,

including the Maiden's Tower and the Shirvanshah Palace, which

is currently undergoing reconstruction. But more than this, the

medieval Inner City used to have its own distinct culture and

set of traditions, many of which are starting to be lost and

forgotten. Reconstructing the ethnographic features of the community

that once lived behind Ichari Shahar's fortified walls is difficult.

Most of today's Azerbaijanis know very little about the history

and traditions of the Inner City. As the older generation passes

on, fewer and fewer people know firsthand about Ichari Shahar's

unique traditions, way of life, national clothing, holidays,

tales and anecdotes. Baku's "Ichari Shahar" (literally,

Inner City), often referred to by foreigners as the "Old

City", is a unique architectural preserve that differs considerably

from the other ancient cities of Azerbaijan. Ichari Shahar [pronounced

ee-char-EE sha-HAR] has many fascinating architectural monuments,

including the Maiden's Tower and the Shirvanshah Palace, which

is currently undergoing reconstruction. But more than this, the

medieval Inner City used to have its own distinct culture and

set of traditions, many of which are starting to be lost and

forgotten. Reconstructing the ethnographic features of the community

that once lived behind Ichari Shahar's fortified walls is difficult.

Most of today's Azerbaijanis know very little about the history

and traditions of the Inner City. As the older generation passes

on, fewer and fewer people know firsthand about Ichari Shahar's

unique traditions, way of life, national clothing, holidays,

tales and anecdotes.

Today, it would be a fair assessment to say that the Inner City's

original community hardly exists. Many of the local residents

have sold their homes and moved elsewhere in Baku and many foreign

companies have located their offices there.

Here historian Farid Alakbarov gives us a feel for what life

was once like in the vanishing community of Ichari Shahar. His

research and insight comes from sources he has discovered at

Baku's Institute of Manuscripts and from his own experiences

of growing up in the Inner City.

______

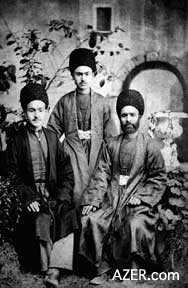

Left: The author's great grandfather, Mashadi Baghir

Alakbarov (bearded), with his two sons, the author's grandfather

Abdul Manaf Alakbarov (center) and Museyib (left) in their garden

in Ichari Shahar. All were sea captains. Abdul Manaf graduated

from the higher Naval School in St. Petersburg. The photo was

taken in 1885. Left: The author's great grandfather, Mashadi Baghir

Alakbarov (bearded), with his two sons, the author's grandfather

Abdul Manaf Alakbarov (center) and Museyib (left) in their garden

in Ichari Shahar. All were sea captains. Abdul Manaf graduated

from the higher Naval School in St. Petersburg. The photo was

taken in 1885.

I was born and raised

in Baku's Inner City, in a house in which previously three generations

of my family had lived. Ever since childhood, I have heard fascinating

stories about Ichari Shahar from my older relatives, my grandfathers

and especially my grandmothers - Hadija Kazimova, my mother's

mother, granddaughter of the famous "Gatir" Zeynalabdin,

and Ruhsara Babazade, my father's mother.

Later I began to collect stories and study various sources related

to the history of the Inner City such as "Old Baku",

a book by the distinguished Azerbaijani actor Huseingulu Sarabski

(1879-1945). Sarabski, who was born in Ichari Shahar and lived

there for many years, wrote vivid descriptions of the events

he witnessed there.

Likewise, the book "What I Saw, What I Read, What I Heard"

by the late writer Manaf Suleymanov (1913-2001) [published in

Azeri Latin in 1996 by Azerbaijan Publishing House] contains

valuable information about the Inner City. Interesting facts

may also be gleaned from the historical works, chronicles, newspapers

and documents archived at Baku's Institute of Manuscripts.

Inner City, Outer

City

According to the archeological evidence, the city of Baku dates

back to at least the early centuries AD. After 1538, Baku served

as the capital of the khanate of Shirvanshah after Shamakhi,

a city 1.5 hours north of Baku, sustained a major earthquake.

That's when the Shirvan Shahs moved their capital to Baku.

From 1747 to 1806, Baku was the capital of a khanate that included

Baku itself and 39 neighboring villages. This independent principality

was called "Badkube" (i.e. wind-beaten), "City

of Winds", and coined its own money.

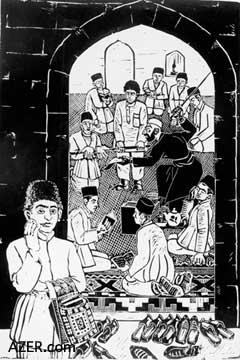

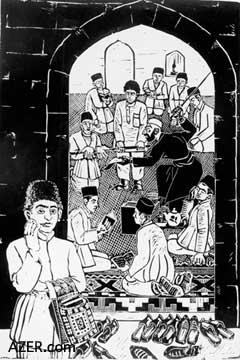

Left: The Mollakhana, the only schools that

existed in the Old City of Baku prior to the establishment of

Russian schools. Youth were beaten (see print) when they failed

at memorizing the Koran, which was in Arabic, a language that

they did not know. Left: The Mollakhana, the only schools that

existed in the Old City of Baku prior to the establishment of

Russian schools. Youth were beaten (see print) when they failed

at memorizing the Koran, which was in Arabic, a language that

they did not know.

During this period,

the entire city was located inside the fortress walls and had

a population of approximately 7,000 people. After the Russians

occupied the city in 1806, and especially during the first Oil

Boom of 1850-1920, Baku grew rapidly beyond its fortified walls.

This is when the expressions "Ichari Shahar" (Inner

City) and "Bayir Shahar" (Outer City) first came into

use. Huseingulu Sarabski writes: "Baku was divided into

two sections: Ichari Shahar and Bayir Shahar. The Inner City

was the main part. Those who lived in the Inner City were considered

natives of Baku. They were in close proximity to everything:

the bazaar, craftsmen's workshops and mosques. There was even

a church there, as well as a military barracks built during the

Russian occupation." Residents who lived inside the walls

considered themselves to be superior to those outside and often

referred to them as the "barefooted people of the Outer

City."

The Inner City consists of many small sections that are demarcated

by winding lanes and narrow streets. Originally, each section,

or block, was named after a neighboring mosque: Juma Mosque Block,

Shal Mosque Block, Mohammadyar Mosque Block, Haji Gayib Mosque

Block, Siniggala Mosque Block, Gasimbey Mosque Block and so forth.

Some of the sections of the Inner City and their mosques were

named after the clans and nationalities that lived there. For

instance, Gilaklar was the place where the merchants from Gilan

stayed; Lezgilar was the street where the Dagestani armorers

and gunsmiths lived. Most of the Inner City's residents were

craftsmen, merchants or seamen. Some of the sections took their

names from certain professions, such as Hamamchilar (Bathhouse

Owners), Bazarlar (Cloth Traders) and Hakkakchilar (Stone Engravers).

Back in 1806, there were 707 shops and craftsmen workshops in

the city, even though the total population was only 7,000. Every

merchant and skilled craftsman had his own store. Their customers

were the traders who came to Baku from various countries. Baku

ships carried goods to and from Iran, Central Asia and Russia.

Centuries - Old

Monuments

The Inner City's ancient monuments include the Maiden Tower,

the Sinig Gala Minaret (11th century), the fortress walls and

towers (11th and 12th century) and the Shirvanshah Palace (15th-16th

century). In addition, the Inner City once boasted 28 mosques,

nine caravanserais, several bathhouses, potable water reservoirs

(ovdans) and a bazaar. Merchants from Central Asia tended to

stay in the 16th-century Bukhari caravanserai, while the Indian

traders preferred the 15th-century Multani caravanserai.

The residents of Baku were fond of bathhouses.

Besides a bath, one could get a massage, enjoy some refreshments

like cool sharbat (fruit drinks) or hot tea, have a snack or

smoke the hookah pipe there. The residents of Baku were fond of bathhouses.

Besides a bath, one could get a massage, enjoy some refreshments

like cool sharbat (fruit drinks) or hot tea, have a snack or

smoke the hookah pipe there.

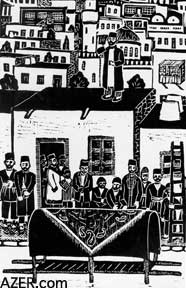

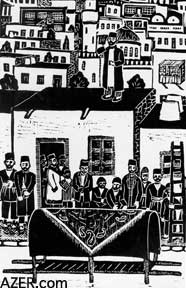

Left: The Carpet Bazaar-bringing to market,

displaying and selling. Note women covered by veil.

Several of Baku's bathhouses are still standing, including the

large 15th-century Haji Gayib bathhouse behind the Maiden's Tower

and the 17th-century Gasimbey bathhouse near the Cultural Department

of the British Council.

While Baku's medieval bazaar no longer exists, you can still

see its columns and arches behind the Maiden's Tower. In the

early 20th century, the bazaar was enlarged to extend from the

Multani and Bukhari caravanserais to the 14th-century Juma Mosque.

European Styles

After the Russian government took control of Baku in the early

19th century, the traditional architectural look of the Inner

City changed. Many beautiful European - type buildings were constructed

during the 19th century and early 20th century, using styles

such as Baroque and Gothic.

One such building, formerly known as the "Chain House",

houses Baku's Institute of Ethnography today. This building's

roof used to have three classical Greek - style statues of women

on display along with two freestanding vases. The pedestals of

all of the statues and vases were joined to each other with a

double iron chain, thus giving rise to the name "Zanjirli

Ev" (Chain House). When I was a child, I used to hear the

older Inner City residents refer to this building as the "Chain

House", but this expression is no longer used today. In

the Soviet period, all of the building's statues were removed,

as were the vases. However, the central statue has recently been

reconstructed.

To the left of the Chain House, as you walk in from the Double

Gates, stands a three - story, early modern style house which

was built in 1903 by my great - grandfather, sea captain Mashadi

Baghir Alakbarov. He lived on the third floor. His brother Museyib,

also a sea captain, lived on the second floor. Mammad Sadikh

Alakbarov, who worked at a bank, lived on the first floor. The

attached one - story building, now covered with grapevines, also

belonged to them and was leased to various shopkeepers.

Left: Traditional Funeral service in the Old City.

Molla on rooftop calls to prayer. Left: Traditional Funeral service in the Old City.

Molla on rooftop calls to prayer.

Inner City businessman

Gatir Zeynalabdin Taghiyev (1837-1915), my mother's great-grandfather

(not to be confused with Taghiyev, the famous millionaire), built

a beautiful two-story Baroque-style building to the right of

the Chain House. Unfortunately, that building was torn down in

the 1970s and replaced by a Soviet concrete block structure that

is known as the Encyclopedia Building.

General Tsitsianov

Sarabski provides interesting information about the history of

the Baku fortress gates, which were built between the 12th and

19th centuries. In the 1930s he wrote: "Recently the Inner

City has acquired a fifth gate, though in the past there were

only four. The most famous of the entrances is the Double Fortress

Gates [Gosha Gala], which was sometimes referred to as the Shamakhi

Gate." According to my elderly relatives, in the past there

was only a single archway there at Gosha Gala, not the two entrances

that exist today, which allow traffic to enter and exit through

separate archways. It seems that Russian General Tsitsianov was

set on capturing the Inner City of Baku through the Gosha Gala

gates. In 1806, the Russian navy landed its troops on the shores

of Baku. General Tsitsianov sought permission from Khan Huseingulu

to permit a garrison of 600 to 1,000 Russian soldiers to enter

the city, under the command of Russian authorities.

At first, the khan agreed and even went out to greet Tsitsianov

in front of the Double Fortress Gates. But while the negotiations

were being carried out (February 2), the khan's cousin Ibrahim

suddenly shot Tsitsianov.

Tsitsianov's soldiers fled. The khan's guard tracked down the

Russians and killed many of them. Then the Baku artillery opened

fire on the Czar's ships, which made a hasty retreat to Sara

Island, off the coast of Baku. The khan beheaded Tsitsianov and

then sent his head to the Iranian ruler Fathali Shah as a gift.

Since Russia was at war with Iran, Huseingulu khan hoped to engage

the Shah's assistance in helping him combat the Czar's army.

However, Fathali Shah did not offer any help. Seven months later,

on September 18, 1806, the Russians returned and this time easily

captured Baku. With his 500 soldiers and 70 cannon, the khan

could not withstand the superior Russian forces under Bulgakov.

Huseingulu fled to Ardabil, a city in what is now Southern Azerbaijan

(part of Iran).

In 1846, the Russians erected a monument

in memory of Tsitsianov, placing it in front of the Double Fortress

Gates where he had been murdered. After the Bolshevik In 1846, the Russians erected a monument

in memory of Tsitsianov, placing it in front of the Double Fortress

Gates where he had been murdered. After the Bolshevik

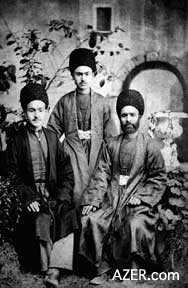

Left: The Zorkhana-a type of traditional

sports club for men. Wrestling was accompanied by music played

on drums, zurna and balaban.

Revolution in 1920, this monument was dismantled and destroyed

because it honored the Czar's army. During the Soviet period,

Azerbaijani historians avoided mentioning these facts and did

not include the Tsitsianov incident in the "official"

version of the history of Azerbaijan. I happened upon this information

by reading some of the old chronicles that are maintained at

Baku's Institute of Manuscripts, especially a chapter called

"The History of the Baku Khanate," found in the book

"Gullistani-Iram (Garden of Paradise) by the famous scholar

Abbasgulu Agha Bakikhanov (1794-1847), himself a descendant of

that last Baku khan.

Gates and Trade

Sarabski provides interesting

information about another famous gate called the Taghiyev Gate

[located near what is now the Academy of Science Presidium].

He writes: "Another gate is situated close to the Double

Fortress Gates, near the Sabir Square." This gate is not

medieval and was built much later (1877) by the Baku merchant

and landowner Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev [a namesake of the famous

millionaire], who had the nickname Gatir Haji Zeynalabdin. Actually,

his nickname relates to this gate. Haji Zeynalabdin owned various

shops where the Sabir Garden and Husi Hajiyev Street are today,

just outside the fortress walls. However, nobody wanted to rent

these shops as they were considered too far on foot from the

bazaar in the Inner City, even though they are part of the heart

of the city today. For quite a long time, Haji's stores remained

empty. Finally, he came up with an idea to ask permission from

the Baku City Council to open a section of the citadel wall and

erect a new gate there.

Left:"Novruz Bayrami sweets" for the New

Year (March 21) from the series of prints by Alakbar Rezaguliyev

called "Old Baku", 1966. Here women prepare pakhlava

and shakarbura. Left:"Novruz Bayrami sweets" for the New

Year (March 21) from the series of prints by Alakbar Rezaguliyev

called "Old Baku", 1966. Here women prepare pakhlava

and shakarbura.

Once people from the Inner City were able to pass through this

gate, Haji's shops began to flourish. That's how Haji got the

nickname "Gatir", which refers to his quick wit, resourcefulness

and persistence. (The word "gatir" literally means

"mule", but implies both "smart" and "stubborn".)

According to newspaper accounts, a heated battle took place in

front of the Taghiyev Gate in 1918, when Armenians were trying

to capture the Inner City. Gatir Haji Zeynalabdin's son, Mammad

Hanifa (1875-1920), nicknamed "Gochu" (meaning "brave"),

commanded the Inner City defenders and succeeded in staving off

the Armenians. [See the article "Baku:

City That Oil Built" in AI 10.2 (Summer 2002).]

Sarabski cites very brief information about the other Inner City

gates. The third gate opened into the courtyard of the Industrial

College [now, Azerbaijan State Economic University]. Wheat and

coal were brought from the Absheron village of Navahi and various

mountain villages in carts and camel caravans and then sold there.

The fourth gate was situated behind Baku's City Hall. The fifth

gate opened from the Governor's Garden near the present-day Philharmonic

Hall.

Baku Clans

The native Inner City dwellers belonged to several different

clans, some of which had very humorous names. For example, some

of the more influential clans were named: Agshalvarlilar (those

[men] who wear white trousers), Toyugyeyanlar (chicken-eaters),

Toyugyemayanlar (those who don't eat chicken) and Bozbashlilar

(literally, the gray-headed, implying bald headed). Each clan

often made disparaging jokes about other clans.

My grandmother used to tell me jokes about the "Bozbashlilar".

The word "bozbash" in Azeri also refers to a favorite

Azerbaijani dish, a soup with large meatballs, chickpeas and

sour plums. So, a very fat person from the Bozbashlilar clan

might jokingly be called "the meatball from Bozbash."

A person with a sour disposition might be known as "the

sour plum from Bozbash." A very small person might be called

"the chickpea from Bozbash." These days, the tradition

of dividing residents into clans has disappeared in Ichari Shahar.

Many young people don't even know which clan their grandparents

belonged to.

Nicknames

In the past, it seems everyone who lived in Ichari Shahar had

a nickname. Often the names were quite humorous. For example,

at one time there were five men living in Baku by the name of

Haji Zeynalabdin. They all went by different nicknames. My grandmother

identified them as: (1) Malakesh (Plasterer), (2) Gatir (Clever

and Stubborn), (3) Spasibo (Thank You, in Russian), (4) Nokar

(Servant) and (5) Pendiryemeyen (Cheese-Hater).

The millionaire philanthropist Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev got

his nickname, "Plasterer" because as a youth he had

worked as a common day laborer doing masonry work. Supposedly,

one day Taghiyev discovered a clay jar filled with golden coins

plastered into the wall of an old house. He took the gold coins

and sold them, and bought a piece of land that, luckily for him,

had an oil gusher. So, the people nicknamed him Malakesh (Plasterer).

However, Taghiyev himself denied that there was any truth to

this tale. Another Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev was nicknamed "Gatir"

(Mule) because he was so smart and persistent in building the

Taghiyev Gate in the citadel wall. Mules are believed to be so

intelligent that they can find water anywhere, even in the desert.

Any person who can make money from "nothing" is often

nicknamed Gatir (Mule).

Writer Manaf Suleymanov tells a curious story about "Gatir"

Haji Zeynalabdin. Haji had a merchant friend who was having trouble

selling a large supply of biscuits (cookies). Haji took a box

of the biscuits and hid his expensive ring inside the box (another

version of the story says it was a five-ruble coin). Then, he

went to the cafe in the Tabriz Hotel, opened the box and began

to munch on the biscuits. Suddenly, he exclaimed: "Look,

what I've found inside the box!" showing off the ring (or

coin) to the people there. People rushed out to buy the biscuits

immediately, and Haji's friend made a huge profit.

The third Haji Zeynalabdin was named "Spasibo" ("Thank

You" in the Russian language). As the story goes, this merchant

found out that Czar Alexander III was planning to visit Baku.

Zeynalabdin decided to play up to him in hopes of receiving a

title, post or medal. Before the Czar arrived, Zeynalabdin repaired

the Russian military barracks in the Inner City with his own

money. The Czar visited the barracks, and afterwards met with

the merchant and told him in Russian, "Spasibo, Zeynalabdin!"

(Thank you, Zeynalabdin!) Then the Czar turned and left, without

bestowing either medal or title. Zeynalabdin had spent enormous

sums of money, but all he got was "Spasibo!" in return!

From then on, Manaf Suleymanov writes, the people living in Ichari

Shahar nicknamed him "Spasibo" Zeynalabdin.

The elderly residents of the Inner City told me that there was

yet another Haji Zeynalabdin who had once been a servant of the

oil baron Haji Zeynalabdin. Gradually, he established his own

business and became wealthy, too. Despite his wealth and newfound

status, the people of the Inner City continued to call him Nokar

Zeynalabdin (Servant Zeynalabdin).

Education

Historical records indicate that a madrasa [a religious secondary

school] was set up in Ichari Shahar in the 11th century. It was

there that the famous Eastern philosopher Baba Kuhi Bakuvi (933-1074)

taught science. Four hundred years later, another distinguished

scholar named Seyid Yahya Bakuvi (died in 1403) founded a Darul-Funun

(university) in the Shirvanshah Palace. However, when the Shirvanshah

state collapsed in 1538 and Baku lost its status as a capital,

these higher-level schools were closed and the cultural life

of the city gradually diminished. The tiny Baku khanate founded

in 1744 could not replicate this sophisticated cultural environment

of an earlier era.

When the Russians descended on Baku in 1806, there were a total

of 12 preliminary and secondary religious schools (maktabs and

madrasas) in the Inner City. According to Sarabski, by the early

1900s, only three remained, and the quality of education had

deteriorated. The common people called these schools "Mollakhana",

meaning "Molla's Home". Some people did not want to

send their boys to the Mollakhana, even for their preliminary

education. They preferred to send them to the less expensive

"private Mollas", who taught only the Arabic alphabet

and the Koran.

Education at the Mollakhanas was based completely upon memorization.

When the youth could not pronounce the Arabic words, they were

beaten with a stick called a "chubug" until they mastered

the pronunciation. Likewise, during the calligraphy lessons,

the teacher would hit the children's fingers when they did not

write correctly. Parents typically supported this approach. When

parents took their sons to the Mollakhana, they used to tell

the Molla: "The flesh is yours, but the bones are mine!"

meaning, "You can beat him, but don't break his bones."

This expression has become an Azerbaijani proverb. In those times,

flogging pupils was common, not only for the Muslim Mollakhanas,

but for the Russian schools as well. Punishment was considered

to be the normal way to make children learn and obey. Before

the Russians came, it was the Mollakhanas who provided the only

education that was available in Baku. Young boys studied the

Arabic alphabet, calligraphy, grammar and arithmetic, and had

to memorize the Koran by heart. Sometimes, they read verses by

Saadi and Hafiz in Persian, and were exposed to a bit of history

from the small tome "Tarikhi-Nadir" (History of Shah

Nadir) and a few other sources.

The musical comedy "O Olmasin, Bu Olsun", (If Not That

One (Bride), Then This One) composed by Uzeyir Hajibeyov in 1911,

provides a humorous reference to this book, "Tarikhi-Nadir".

One of the musical's comic characters, the merchant Mashadi Ibad,

comments on how his friend has sprinkled his conversation with

pretentious words and phrases in Turkish, Russian and French.

"I've read nearly half of 'Tarikhi-Nadir'," Mashadi

Ibad says, "but I still can't understand what you're trying

to say!" The fact that this history text is so small makes

the statement even more humorous.

Water Supply

Since Baku is located on arid land, its residents have always

struggled to have an adequate water supply. [See "Water

- Not a Drop to Drink, How Baku Got its Water" by Ryszard

Zelichowski, "Baku's

Search for Water" by Mammad Mammadov, and "Taghiyev's

Commitment to the Water Problem" by Manaf Suleymanov

in AI 10.2 (Summer 2002). Search at AZER.com.]

Beginning in the 11th century, the Inner City had three underground

water supply systems built of stone and clay pipe. In the 19th

century, this underground pipeline was named Naghi Kuhulu, meaning

"The Pipeline of Naghi"; it served the Inner City residents

until the beginning of the 20th century. The water flowed in

from wells and springs situated throughout the city, then collected

in a special reservoir inside a building named Shirin Ovdan (Sweet

Water House), located near the Shirvanshah Palace.

Sarabski writes that sometimes the pipes of the Ovdan clogged

up, stopping the flow of water. A very kind, skilled person named

Jumru Aghamali always came to the rescue. He was very small,

slender and quick, and could descend into the narrow water pipe

and clean it out.

Sarabski writes: "Jumru Aghamali never asked for any payment

for this work as he believed it was pleasing to God. After Jumru

died, nobody continued his work and the Shirin Ovdan fell into

disuse." Despite Jumru's generosity, he was still labeled

with the nickname "Hezar pesha, kam maya", which means,

"a thousand jobs, little money". Many families tried

to find solutions to the city's water problem by digging their

own private wells in their courtyards. One of the outer walls

of the ovdan used to have a plaque identifying it as: "Medieval

Ovdan. This monument of architecture is under the protection

of the State." However, the plaque no longer stands.

Underground Tunnels

According to medieval sources, there used to be several underground

tunnels located under the Old City. Some of them were constructed

in the 15th century by the Shirvanshahs to serve as escape routes

from the palace complex.

Another underground tunnel was built by Gatir Haji Zeynalabdin

at the beginning of the 20th century, connecting two of his residences:

the one that used to stand where the Encyclopedia Building is

now and another one located on what is now Aziz Aliyev Street

where the Yin Yang Chinese restaurant stands. Haji wanted his

family members to be able to move between the two houses, which

were approximately 100 meters apart on either side of the citadel

wall.

My grandmother told me that she had often walked through this

tunnel during her childhood. During the Bolshevik Revolution,

the owners of these residences fled or were killed. Their buildings

were subdivided into many small apartments, and the tunnels were

forgotten until the 1970s, when archeologists rediscovered the

tunnel, studied it and then went on to other projects, leaving

their excavation work exposed. Somehow thieves figured out that

the tunnel led right up into a jewelry store (now where the Yin

Yang Restaurant is located).

During the night, the thieves secretly began to dig and clean

out this underground tunnel. Eventually, they succeeded in breaking

into the jewelry store and ran off with some precious jewels.

Once the Baku newspapers wrote about the crime, the tunnel was

filled in.

Sports Competitions

One of the Inner City's entertainment areas was the Zorkhana,

a type of stadium where athletic competitions took place. Baku's

Zorkhana dates back to at least the 15th century. Few people

know about it, but this underground vault was located just a

few steps from the Bukhari and Multani caravanserais, towards

the Maiden's Tower.

Similar to sports clubs today, men paid an entrance fee to participate

in various competitions, including weightlifting, wrestling and

boxing. There were contests accompanied by a trio of musicians

who performed traditional Eastern instruments like the kamancha

(stringed instrument), zurna (wind instrument) and naghara (drum).

Most of these melodies have long since been forgotten. However,

one by the name of "Jangi" (War) is still performed

prior to the opening of national wrestling competitions (Gulash).

Young men could test their strength against professional wrestlers

such as those who came from Tabriz, Ardabil, Sarab and other

cities of Southern Azerbaijan (in Iran). Sarabski writes about

one wrestler nicknamed "Altiaylig Abdulali" (Six-Month

Abdulali) who took on all these youth. Before each match, the

famous musician Haji Zeynal Agha Karim would perform a song glorifying

the wrestler. Altiaylig Abdulali would untie his belt, toss his

hat on the floor and come out onto the stage grinning. The young

amateurs approached him one by one. When Altiaylig was finished

wrestling, the spectators would give him various denominations

of money such as three, five or even ten rubles, a considerable

sum of money at the time.

The Zorkhana also functioned somewhat like a fitness club. When

no competitions were taking place, men went there to do exercises

and use sports equipment.

Another competition involved lifting, hurling and catching heavy

millstones. The event was referred to as "Mil Oyunu"

(Millstone Game). The competitors were usually accompanied by

a naghara player, who gradually increased the tempo by beating

the drum faster and faster.

Baku residents also enjoyed attending poetry readings (She'r

Majlislari) and mugham sessions (Mugham Akhshamlari). Poets,

musicians and others often gathered together to perform lyrical

verses (rubai and gazals) and listen to mugham (Eastern modal

music). Food, drinks and sweets were served.

The residents of the Ichari Shahar were fond of "meykhana"

(literally, wine house), an improvisational musical/literary

form common to Baku and its adjacent villages. [See "Meykhana:

Azerbaijan's Own Ancient Version of Rap Reappears" in

AI 4.3 (Autumn 1996).] Meykhana competitions are still popular

in the villages around Baku, although during the Soviet period

they were banned for being too controversial.

Meykhana takes its name from the Eastern pubs where these performances

were carried out. The contest involved two or more poets exchanging

verses back and forth in an extemporaneous fashion, sometimes

joking and disparaging one another. Their rap-like songs often

touched on social and political issues of the time. At the end

of the contest, the audience determined which poet had improvised

the most elegant and clever verses and declared him the winner.

Another favorite pastime among the youth in Baku was raising

pigeons. They would keep scores of pigeons in pigeon lofts, usually

on the roofs of their homes. Every morning, the owners would

climb up on the roof, feed the pigeons and then whistle loudly

to send them off into flight. You can still find a few pigeon

fanciers in the Inner City today.

Nard (backgammon) was a favorite game in the Inner City. Every

family had a set, and the men would often sit and play the game

for hours. Some people also played shatranj (chess) and dama

(checkers).

Children played various games such as Chumrug-Chumrug, Besh-Onbesh,

Usta-Shayird, Dash-Bash, Gizlanpach, Oghru - oghru, Shumagadar

and others that are forgotten now. Of these games, only Gizlanpach

(hide-and-seek) is still widespread today. Banovsha (Violet),

known in other parts of the world as "Red Rover" or

"Octopus Tag", was also a popular game in Ichari Shahar.

Favorite Dishes

The Inner City dwellers liked meat and often referred to it as

"jan" (life). My grandmother once told me a funny proverb

that divided various foods into categories according to their

nutritional value and taste: "Go to the market and buy 'jan'

(life, specifically meat); if 'jan' is not available, buy 'jarimjan'

('half-life', that is, eggs); if 'jarimjan' can't be found, buy

'badimjan' (eggplant, that is, 'poor man's food')".

On holiday mornings, men met their friends in special cafes called

"khashkhana". There they enjoyed "khash",

a hearty, gelatinous soup made from calf's or sheep's feet and

seasoned with vinegar and chopped garlic. Eating khash with friends

was a popular activity back in those days, just as it is today

in Baku. Certain dishes were typical of the Inner City and its

adjacent villages: dushbara (soup made with tiny lamb dumplings),

shorgogal (a round puffed cookie with salt and spices), and chudu,

a puff pastry stuffed with minced meat and sprinkled with sugar

and sumac). These dishes were typically not prepared in other

areas of Azerbaijan.

Traditional Dress

As far as traditional dress and appearance were concerned, each

adult man had to wear a mustache and the national hat ("papag")

on his head. Up until the early 20th century, it was considered

shameful to appear in the street without a mustache, although

Westernized citizens often infringed on this rule. When men were

involved in a serious argument, they would threaten each other:

"I'll cut off your mustache!"

The importance of the hat was emphasized by the following proverb:

"Kishinin papaghi bashinda olar."

A man's hat is always on his head.

The hat was considered to symbolize the man's honor. If someone

touched a man's hat or grabbed it off his head, it was considered

a great affront and could even result in bloodshed.

Baku residents developed a set of traditions in regard to giving

charity to the poor. During the Muslim religious holidays, the

wealthy (and even those who were not so wealthy) would organize

an "Ehsan", or charity dinner for the poor.

My grandmother told me that in those days all of the doors of

her grandfather's home were opened. On the first floor, he filled

long tables with various hot dishes and sweets. Anyone from the

street could come in, sit and eat as much food as he wanted.

The servants took away the empty plates and brought in new dishes.

Hundreds of houses in Baku provided Ehsan during the holidays.

Sometimes the merchants would place the charity tables in the

streets in front of their shops. Back then, if a person seemed

eager to get some food or service without payment, he would be

reprimanded:

Bu saninchun Ehsan deyil.

It's not an Ehsan for you.

Gochus

Gochus were the bullies or gangsters of the Inner City. These

glowering, pompous individuals sported big mustaches, dressed

in national costumes and armed themselves with revolvers and

daggers. When they walked through the city, no one dared confront

them. The average person living in Baku came to fear them very

much. Gochus appeared in Baku at the end of the 19th century,

in response to the Georgian gangsters called "Kintos",

who were engaged in kidnapping and robbery and threatened wealthy

Baku residents.

Since the city's police couldn't deal with the Kintos effectively,

wealthy people began recruiting and arming strong, brave men.

Soon, the Kintos disappeared from Baku, never to return again.

The Baku millionaires saw the effectiveness of the gochus and

began to use them as personal bodyguards. When the businessmen

of the Inner City were involved in a quarrel, they often sent

their gochus out to fight each other. Sometimes this resulted

in a shooting match. It wasn't long until some of these gochu

groups turned into a kind of mafia.

Manaf Suleymanov wrote that a group of gochus kidnapped the famous

Baku millionaire Agha Musa Naghiyev, who was known as a miser.

The gochus demanded 10,000 golden rubles for his release and

threatened to carve him up into little pieces. Agha Musa firmly

replied: "I can pay only 950 rubles. Of course, you can

cut me up into pieces, but then you won't get anything at all."

The gochus understood that Agha Musa would rather die than part

with his 10,000 rubles, so they released him for the ransom that

he had negotiated.

It's important to know that not all gochus were gangsters or

killers or private security agents of millionaires. Some of them

were rich young men who were simply bored at home. Seeking to

have a good time, they would dress up in national costumes, wear

daggers or revolvers and go out into the streets looking for

an adventure, just to show their courage and strength.

Usually, they ended up quarreling with each other and threatening

the poor, helpless people in the streets. For example, they would

approach a very poor man and cuff him on the head, saying things

like: "How is it that you passed me by and did not address

me by saying, 'Hello Sir?'" or "How dare you trim your

mustache?" or "Where's your hat?" or even "Why

do you stand in front of me with such a scowl?"

There were also "good gochus" who protected their communities

from criminals. Curiously, it was the gochus who helped save

the Inner City during the Armenian and Bolshevik massacre of

March 1918, as they were primarily the only armed and organized

Azerbaijanis in the city at that time.

Businessman Teymur Ashurbeyov, who lived in the Outer City, and

Mammad Hanifa Taghiyev from the Inner City mobilized their gochus,

and then rallied and armed many other citizens. They sent these

troops in against the Armenian Dashnak military forces. As a

result, the Inner City and a few streets of the Outer City were

spared from the massacre, while thousands of other Azerbaijanis

were slaughtered elsewhere.

Mulberry Tree

There used to be a very large, old mulberry tree in the Inner

City, located behind the Juma Mosque. People believed that it

was several hundred years old. On hot summer days, men would

sit under it drinking tea and playing backgammon.

The tree was such a well-known landmark that people used to say

things like: "Let's meet at the Mulberry Tree" or "I

live to the left of the Mulberry Tree." A popular song was

even written about this tree as a symbol of the Inner City.

About 25 years ago, the tree was cut down when some construction

work was being done. The local people were very upset about this

loss. Several months later, someone decided to plant a new mulberry

tree there. Back then, Baku residents cared about their city

and wanted to maintain its historical look and landmarks. But

now, the new tree has been cut down, too. There are simply not

enough of the native residents of the Inner City remaining there

who understand its significance.

The history of the Inner City during the first Oil Boom (1850-1920)

is extremely rich and engaging. The memories of Huseingulu Sarabski,

Manaf Suleymanov, as well as the stories of the elder Inner City

residents, the old newspapers and magazines, and many other sources

reveal interesting facts about the history of Baku. These details

must be carefully collected, reconstructed and investigated by

today's historians. Now that the Soviet period has ended, we

have the enormous task of researching the history of our nation

and trying to set the record straight.

Dr. Farid Alakbarov, a frequent

contributor to Azerbaijan International, is chief scientific

officer in the Department of Arabic Manuscripts at Baku's Institute

of Manuscripts. His speciality is researching Azerbaijani manuscripts

written in the Arabic script. To read other articles by Alakbarov,

SEARCH at AZER.com. Several of his articles may also be found

in Azeri Latin at AZERI.org,

a Web site that features Azeri language and literature.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(10.3) Autumn 2002.

© Azerbaijan International 2003. All rights reserved.

|