|

Autumn 2003 (11.3)

Music Therapy

What

Doctors Knew Centuries Ago

by Farid Alakbarov

Although

skeptics may doubt the curative powers of music, scientists have

known for centuries that music does contribute to the healing

process. In plants, music has been proven: modern scholars have

established that the regular playing of classical music greatly

enhances the growth and development of plants. Tests have been

carried out using Western classical music such as Mozart, Beethoven

and Chopin. If music can affect the well being of plants, should

it come as a surprise that human health can be affected as well.

Here's what medieval scientists and physicians from Azerbaijan

and the region had to say about the curative powers of music. Although

skeptics may doubt the curative powers of music, scientists have

known for centuries that music does contribute to the healing

process. In plants, music has been proven: modern scholars have

established that the regular playing of classical music greatly

enhances the growth and development of plants. Tests have been

carried out using Western classical music such as Mozart, Beethoven

and Chopin. If music can affect the well being of plants, should

it come as a surprise that human health can be affected as well.

Here's what medieval scientists and physicians from Azerbaijan

and the region had to say about the curative powers of music.

Many centuries ago, physicians

were well aware of the potency of music. Seven hundred years

go, Azerbaijani scientist Safiyaddin Urmiyyayi (13th century)

wrote treatises, explaining his ideas about the antidotal powers

of music in "Message to Sharafaddin" and "The

Book On Musical Tones".

His works name some of the modal scales of that early epoch,

such as Metabil, Erani, Tanjiga and Segah. To alleviate tiredness

and provide relief from neurosis, to lift one's spirits or to

induce sleep, our ancestors used to listen to music performed

on the ancient Eastern musical instruments such as the rubab,

ud, dutar, tambur, ney, mizmar, surnaya, chang, shahrud and kanun.

In Iran and some of the Arabian countries, Safiyaddin Urmiyyayi

is considered to be the "Father of Mugham" (the genre

of traditional modal music). He was the first person to develop

a scientific theory for this genre, create musical terminology

and identify and teach modal scales. He wrote about the positive

influence of music on human health. During the century that followed,

another Azerbaijani musician Abdul-Kadir Maraghayi (1353-1433)

continued his work.

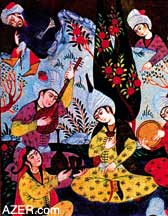

Below: Medieval physicians recognized the

power of music and nature to relax and cure their patients. Miniature

from Baku Institute of Manuscripts.

Between the 9th and

14th centuries, the medical properties of music were elaborated

by well-known scientists such as Abu Nasr al-Farabi, al-Khorezmi,

Abu Reyhan Biruni, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Safiyaddin Urmiyyayi

and others. Between the 9th and

14th centuries, the medical properties of music were elaborated

by well-known scientists such as Abu Nasr al-Farabi, al-Khorezmi,

Abu Reyhan Biruni, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Safiyaddin Urmiyyayi

and others.

What did they define as the curative nature of melodies? The

Great Turkic scholar Abu Nasr al-Farabi (873-950) in his "Great

Book About Music" observed: "Music promotes good mood,

moral education, emotional steadiness and spiritual development.

It is useful for physical health. When the soul is not healthy,

the body is also ill. Good music, which cures the soul, restores

the body to good health."

"Do you have a headache? Relax beside a flower bed or a

trickling fountain, or invite a musician to come and perform

so you can fall asleep to the gentle sounds of dutar (Eastern

stringed instrument)!" advised the great physician Ibn Sina

(980-1037). Seven centuries later Mahammad Yusif Shirvani (18th

century) prescribed melodies of stringed instruments for those

who were suffering from melancholy and insomnia.

The well-known doctor Sultan Giyasaddin in his work "Kitab

as-Sinaat" (18th century) challenged his colleagues to study

music, noting that "scholars of India recommend that physicians

study melodies and the theory of music. This science is necessary

for the doctor, just like his search to understand the subtleties

of diagnosing the pulse. In addition, some illnesses may be cured

when the patient listens to certain melodies."

Some Indian melodies are still performed in Azerbaijan, such

as the mughams known as Humayun and Maur-Hindi. Indian melodies

were brought to Azerbaijani by numerous Indian traders and colonists

who came in Azerbaijan and stayed here permanently. For example,

many villages in the Mughan lowlands of Azerbaijan were settled

by Turkic tribes who came here from northern India and Pakistan

in the 17th-18th centuries. Some of the men had fought in the

armies of the Safavid shahs who, in turn, granted them land in

Azerbaijan for their loyal services.

Following the advice of Sultan Giyasaddin, the physicians of

the Middle Ages tried to understand what was known about the

curative powers of music (elm al-musigi), but it was not so easy.

Music was such a subtle and exacting science that the Central

Asian scientist al-Khorezmi (783-850) included it in a section

of mathematics, specifically in the discussion of his famous

work on algebra!

"The Musical Treatise" by Abdul-Kadir Maraghayi and

"Large Book On Medicine" by Abu Reyhan Biruni (973-1048)

are both filled with mathematic, geometrical figures, sketches

and drawings of musical instruments. But it seems that physicians

did not mind spending time to study the powerful effects of music,

as they considered it invaluable for the health of their patients.

Music Treatment

What kind of music did doctors use to treat their patients in

medieval Azerbaijan? At that time, 12 basic kinds of mugham and

12 musical modes were known. Maraghayi wrote: "Turks prefer

to compose in the "usshag", "nova" and "busalik"

mugham styles, though other mughams also are included in their

compositions".

Sharaf-khan Bidlisi (16th century) described a feast of the Azerbaijani

ruler Shah Ismayil Safavi: "Sweet-voiced singers and sweet-sounding

musicians started singing a usshag melody with both high and

low pitched voices, and then the tears of the harps and lyres

kidnapped reason and logic from the listeners, both great and

the small."

Music promoted the development of a number of mystical sciences.

In the 13th century, the Turnini Dervishes (Mavlavi), considered

that knowledge of God was possible only when they fell into a

trance brought on by listening to special music and which slowly

turned into a mystical dance. The Azerbaijani philosopher Sukhravardi

(died in 1191) who was close to the Sufi mystics wrote: "Know

that those engaged in the exercise of the spirit sometimes use

a gentle melody and pleasant incense. Therefore, they are able

to obtain a spiritual light that is habitual and sustained for

a long time".

At the end of the 10th century, a group of the Shiite philosophers

(Brothers of Purity) had developed a science about the relationship

between music and various elements of a nature: animals, herbs,

minerals and color. According to this theory, each musical sound

corresponds to a specific color and is associated with a certain

mineral, herb and animal. Some sounds were equated with bright

colors, bright metals, beautiful flowers and active animals.

Our ancestors believed that musical instruments were similar

to medicinal plants and aromatic spices. The tar (stringed instrument)

was compared with health-promoting and fragrant saffron. The

naghara (small drum) was identified with the curative powers

of cloves or ginseng. The ud (stringed instrument) was associated

with the soothing effect of valerian or lemon balm. The zurna

(a nasal-sounding wind instrument) was associated with strong

coffee.

The medical properties of these and other instruments are provided

below. Information about the healing properties of instruments

is documented in such books as "Gabusname" by Keykavus

Ziyari, and from books by Abdul-Kadir Maraghayi, Farabi and Safiyaddin

Urmiyyayi. Primarily, however, this information comes from Azerbaijani

verbal folklore of the 19th-20th ashugs (minstrels), a large

heritage of which has been collected and kept at the Baku's Institute

of Manuscripts.

TAR

The melodies performed on tar were considered useful for headache,

insomnia and melancholy, as well as for eliminating nervous and

muscle spasms. Listening to this instrument was believed to induce

a quiet and philosophical mood, compelling the listener to reflect

upon life. Its solemn melodies were thought to cause a person

to relax and fall asleep.

The author of "Gabusname" (11th century) recommends

that when selecting musical tones (perde) to take into account

the temperament of the listener. He suggested that lower pitched

tones (bem) were effective for sanguine and phlegmatic persons,

while higher pitched tones (zil) were helpful for those who were

identified with a choleric temperament or melancholic temperament.

NEY

The gentle sound of the ney (wind instrument that produces a

sound resembling the flute) calms the nervous system, reduces

high blood pressure and tiredness, and promotes good sleep. The

ney is believed to awaken a reflective mood, causing a person

to appreciate and enjoy nature. It is linked to deep philosophical

ideas.

UD

Our ancestors considered that listening to the sound of ud (pronounced

as "ood") was an excellent remedy against headache

and melancholy, reducing muscle spasms and creating a strong

calming action. The ud was one of the most widespread and favorite

instruments in medieval Azerbaijan. It is related to the ancient

Greek harp. Instruments, similar to the ud are depicted in ancient

Egyptian frescos.

SAZ

Music performed on the saz (national stringed instrument) calms

the nervous system and enhances and lifts one's mood. It is useful

in treating melancholy and for eliminating feelings of pessimism.

ZURNA

This wind instrument is said to stimulate the spirit of battle

and sometimes even to instigate aggression and war-like characteristics.

The sound of zurna helps to reduce apathy, indifference, and

increase the blood pressure.

NAGHARA

This instrument helped the doctors to deal with bad mood, melancholy,

intellectual and physical exhaustion, as well as low blood pressure.

It was considered that the Naghara could substitute for some

medicinal plants and tones like spicy cloves. The rhythmic beating

of the naghara is believed to lead to the strengthening of the

heart. The naghara is described in the Early Middle Age Azerbaijani

literary epic, "Kitabi Dada Gorgud" (The Book of my

Grandfather). Instruments resembling the Naghara were also well

known in ancient Egypt.

Thus, according to the rich scientific and musical heritage of

our ancestors, it seems that not only did they listen to music

for enjoyment and entertainment, but they perceived music a potent

force in the prevention and treatment of various diseases.

Dr. Farid Alakbarov heads both

the Department of Translation and the Department of International

Relations at the Institute of Manuscripts in Baku. His articles

about medieval manuscripts can be found by searching at AZER.com.

Some of Dr. Alakbarov's articles published in Azerbaijan International

have been translated into Azeri (Latin script). SEARCH at AZERI.org.

From Azerbaijan International (11.3) Autumn 2003.

© Azerbaijan International 2003. All rights reserved.

|