|

If alphabets could speak, they would tell you that much more goes into their design than just aesthetics. Historical precedence, religion and politics all play an important role in their final shape. Azerbaijan's new Latin alphabet is no exception. On December 25, 1991, Azerbaijan's Milli Majlis (Parliament) officially adopted a modified Latin script for their Azeri alphabet. It was one of the first decisions of the new Parliament-and one, needless to say, that met with immense controversy. Alphabet changes are not new to Azerbaijan; this was the fourth time this century it had been changed. Latin replaced Arabic in 1928, followed by Stalin's imposition of Cyrillic in 1938, which remained until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. No matter how revolutionary and daunting the task, it was not a new idea. In fact, if you count the slight modifications and "corrections" that have been made to individual letters in both Latin and Cyrillic during this century, then there have been at least 10 occasions when the alphabet has been changed.

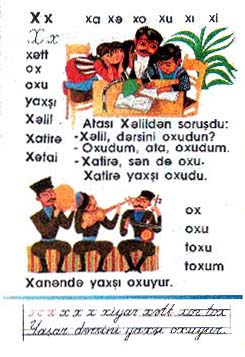

Writer and playwright Akhundzade (who died in 1878) advocated for change as did Jalil Mammadgulzade, editor of the satiric magazine, "Molla Nasreddin, " and in the early 1900s, but both of these reformers were severely attacked by the clergy. In 1918, the question again arose with the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan. However, this government was so short-lived (only 23 months) that it did not have sufficient time to resolve the issues of the alphabet change. In 1920, the Bolsheviks took power and pressured for Latin. Latin was beginning to be used simultaneously with Arabic. For example, the newspaper "Yeni Yol" (New Way) used Latin exclusively. Above: First alphabet primer by Yahya Karimov, introduced in 1992. In 1924, Nariman Narimanov, a leader in the Bolshevik government that was set up in Baku, succeeded in passing a resolution for all official documents to be written in Latin. In 1926, the First Congress on Turkology was held in Baku and scholars from all over the world participated. At this conference, the conclusion was reached that, given the sound patterns in the Turkic languages, Latin was the optimal alphabet to express these sounds. Ataturk began a successful alphabet reform in Turkey in 1928, replacing Arabic with a modified Latin script which is still in use today. In 1928, a committee known as "Yeni Alif" (New Alphabet) was established in Moscow to deal with alphabet issues, and that same year, Latin was adopted for all the Turkic people of the USSR (Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrghyzstan and Uzbekistan). At that time, the alphabet was sufficiently standardized among these Soviet-Turkic languages to facilitate communication. Such legislation fostered the cultural union of the Turkic people. Cyrillic Imposed Thus, for many Azerbaijanis, reclaiming the Latin script in 1991, symbolized the restoration of a heritage that had been stolen from Turkic-speaking people under Soviet rule. In the 1970s and 1980s, a group of Azerbaijani writers, including Anvar Mammadkhanli, Ilyas Afandiyev, Aydin Mammadov, Akram Aylisli, Elchin, Vagif Jabrayilzade and Mati Osmanoglu occasionally raised the issue of reclaiming the Latin alphabet in their speeches and written works. Effect Of "Black

January" According to Firidun Jalilov, a Turkologist who helped spearhead the Latin movement, a great depression descended on the people after the "Black January" events. It was so incomprehensible and shocking that tanks from their own country, the Soviet Union, had descended upon their own city and killed innocent bystanders who happened to be in their path. Officially, 132 people died that night. Unofficially, the figures are much higher. According to Jalilov, "We needed something to spur us on, to unite us in our quest for independence after this great tragedy. That's when some of my friends, like Sabir Rustamkhanli, and I came up with the idea of pursuing one of two possibilities-either starting a campaign to rid ourselves of the Cyrillic alphabet or finding a way to modify our Russified last names." [This refers to dropping the Russian suffix -ov, -ova, -yev or -yeva which had been imposed everywhere during the Soviet period, and replacing it with Turkic endings, especially -zade, -li and -qiz]. Jalilov concluded that the bureaucratic procedure needed for changing surnames was too cumbersome, and would require considerable time, energy and money. So he and his friends decided to push for adopting the Latin alphabet! In March 1990, Jalilov published a newspaper article about the alphabet in the newspaper "Azerbaijan," which at that time belonged to the opposition (though today it is the main government newspaper). This generated a strong reaction. Many other articles and discussions followed. In addition to Latin, Cyrillic and Arabic, even Old Runic (an alphabet of the 7th and 8th century) was discussed as a possibility, Latin, however, generated the most interest. Parliament Opts For

Latin Some religious leaders claimed that the Arabic script was "the alphabet of Islam." With financial backing from neighboring countries, they began setting up coursed to teach the Arabic script in secondary schools and privately. This campaign continued until 1993-94. This confused some people into thinking that, by learning the Arabic script, they would be able to understand the Arabic language. Others feared that when symbols for specific letters changed, the sound would change, as well. However, when pro-Arabic contenders saw that their arguments were being refuted scientifically and they were losing the debate, they united with pro-Cyrillic forces against those advocating Latin. One of the most ardent anti-Latin forces in the country was the Azerbaijan Social Democratic Party. It should be noted, however, that both Presidents Abulfazl Elchibey and Heydar Aliyev were strong advocates for the new Latin. The government was supported by the foremost linguistic institution and by individual professional linguists such as Tofig Hajiyev, Firidun Jalilov, Kamil Vali Narimanoglu, Suleyman Aliyarly, Sabir Rustamkhanli and others, all of whom published numerous articles arguing that the Latin alphabet was the most suitable for representing all specific Azeri-specific sounds. Slow Transition Later the same year Yahya Karimov's primer "Alifba" came out in Turkey and was brought to Azerbaijan. Since then, all newly-printed textbooks and other teaching materials for schools have been printed entirely in the Latin script. For example, although old Cyrillic textbooks are still used in upper grades, the new ones are in Latin. Each year, the textbooks for the next higher level are printed in Azeri Latin (the project has reached the fifth level now). This means that students in the junior grades are not even familiar with Cyrillic and that Latin is their native alphabet. New Trends Another first since the adoption of Latin: the Speaker of the Milli Majlis, Murtuz Alasgarov, officially stated in Parliament (April 1997) that the implementation of the new alphabet should be accelerated nationwide. Following his statement, leading national papers ("Khalg Gazeti" and "Azerbaijan") have begun to print presidential decrees and parliamentary news (which is sometimes a major article) in Latin. No longer does AzTV (Azerbaijan TV) use the apostrophe when presenting Latin. The apostrophe was left over from Cyrillic (from Arabic), but is no longer used now in Latin. Now, that too has been removed, at least in popular usage on television. People are becoming more familiar with what Azeri Latin looks like. For example, in May 1995, one company had translated 40 pages of text and documents and taken them to a Notary's office for certification. After looking at both the English and Azeri Latin copy, the Notary handed them back, demanding that they both be translated, as they were both written in a foreign language. More and more books are being published, though the process is still extremely slow. There are story books and folktales for children. some of the more recent publications include two volumes of Fizuli's poetry, a folklore anthology entitled "Azerbaijani Customs and Traditions," Aziza Jafarzade's new novel "Zarintaj Tahira," Vahid's gazelles (a form of poetry) and a few scientific books. Still Cyrillic is primarily the alphabet of publishing. Sometimes the cover is printed in Latin, but the contents inside are Cyrillic. Factors facilitating the progress towards a more widespread implementation of the Latin script:

All of these factors support the belief that the Latin alphabet is establishing itself in Azerbaijan, not necessarily as rapidly as some might wish, but steadily and irreversibly. Firidun Khalilov and Jala Garibova contributed to this article. From Azerbaijan

International

(5.2)

Summer 1997. Home | About Azeri | Learn Azeri | Contact us |

Historical Precedence

Historical Precedence